Architecture and Design#

While architecture sets the overarching structure and direction of the software system, detailed design delves into the nitty-gritty details, transforming abstract ideas into executable instructions for development teams. Both are crucial phases in the software development lifecycle, working in tandem to ensure the creation of a robust, functional, and scalable software product.

Architecture:#

High-Level Structure and Organization:

Architecture provides a bird’s-eye view of the system, outlining its major components, their interactions, and the overall structure. It defines the system’s boundaries and highlights the key elements that make up the entire software.

Defines the System’s Components and Their Relationships:

It identifies the main components of the system and their roles in fulfilling the system’s purpose. Describes how these components interact, including the flow of data, control, and communication between them.

Guides the Development Process:

Acts as a roadmap for the development team, providing a clear vision of the system’s structure and behavior. Helps in making crucial decisions about technology choices, scalability, and other architectural considerations.

Ensures the System Meets Requirements:

Architecture is aligned with the functional and non-functional requirements of the system, ensuring that it satisfies the needs of stakeholders. Acts as a blueprint for development, serving as a reference to validate that the final product aligns with the initial vision.

Design:#

Implementation Details of Individual Components:

Detailed design zooms into individual components identified in the architecture, providing specifics on how each component will be implemented. It may include decisions regarding programming languages, frameworks, and libraries.

Internal Structure, Interfaces, Algorithms, and Data Structures:

Specifies the internal workings of each component, detailing how data is processed, algorithms employed, and the data structures used. Defines the interfaces between different components, specifying how they communicate and exchange information.

Translates High-Level Architectural Decisions:

Takes the abstract concepts outlined in the architecture and translates them into concrete instructions for developers. Bridges the gap between the high-level architectural vision and the low-level implementation details.

Integration Points and Dependencies:

Identifies where different components will be integrated and how they depend on each other. Provides insights into potential challenges and solutions related to integration points.

Some Architectural Styles#

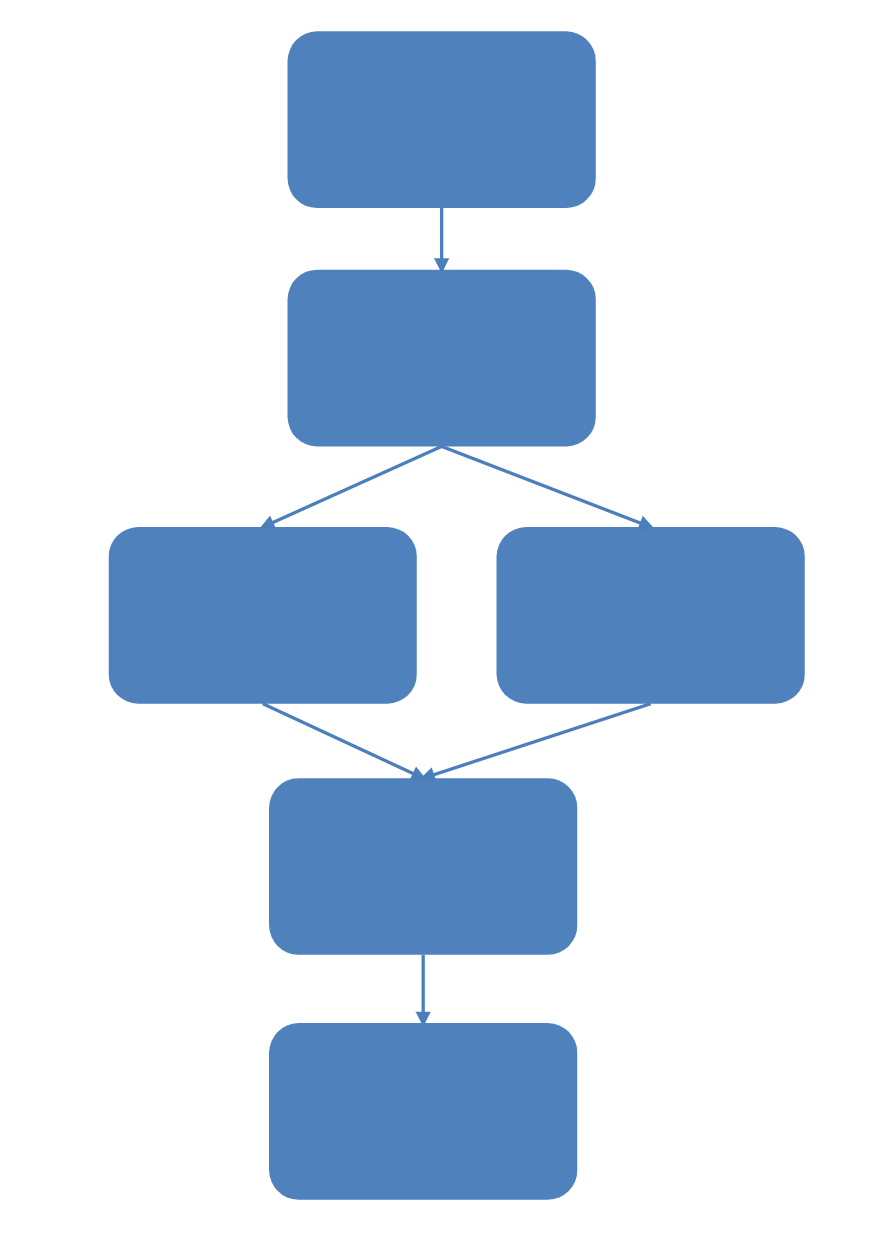

Pipeline or Workflow architecture#

A pipeline or workflow architecture is a systematic approach to organizing and executing complex tasks or processes in software development, particularly in data-intensive research or scientific workflows. This architecture structures the software as a sequence of interconnected processing stages or tasks, creating a streamlined flow for data to move through the various steps of the process. This organization helps manage and optimize the execution of tasks, making it especially useful in scenarios where data processing and analysis involve multiple, interdependent steps.

Fig. 51 Pipeline#

Key characteristics of pipeline or workflow architecture include:

Sequential Processing:

Tasks are arranged in a sequential order, forming a pipeline where data flows from one stage to the next. Each stage performs a specific function or operation on the input data, leading to the gradual refinement or transformation of the data as it progresses through the pipeline.

Modularity and Reusability:

Each stage in the pipeline is designed as a modular component with a well-defined purpose. Modular design promotes reusability, allowing developers to easily replace or update individual components without affecting the entire pipeline.

Interconnectivity:

Stages in the pipeline are interconnected, with the output of one stage serving as the input to the next. This interconnectivity enables a seamless and efficient flow of data through the entire workflow.

Parallelism:

In some cases, certain stages of the pipeline can be executed in parallel to improve overall processing speed and efficiency. Parallel execution is particularly beneficial when dealing with large datasets or when multiple tasks can be performed concurrently without dependencies.

Error Handling:

Pipeline architectures often include mechanisms for error handling and fault tolerance. If an error occurs at any stage, the pipeline can be designed to handle exceptions gracefully, log errors, and potentially retry or skip problematic stages.

Visualization and Monitoring:

To facilitate understanding and management, pipeline architectures often include tools for visualizing the workflow. Monitoring capabilities help developers and operators track the progress of data through the pipeline, identify bottlenecks, and troubleshoot any issues.

Scalability:

Pipelines are designed to be scalable, accommodating changes in data volume or computational requirements. Scalability is crucial for handling large-scale data processing tasks, common in scientific research or data-intensive applications.

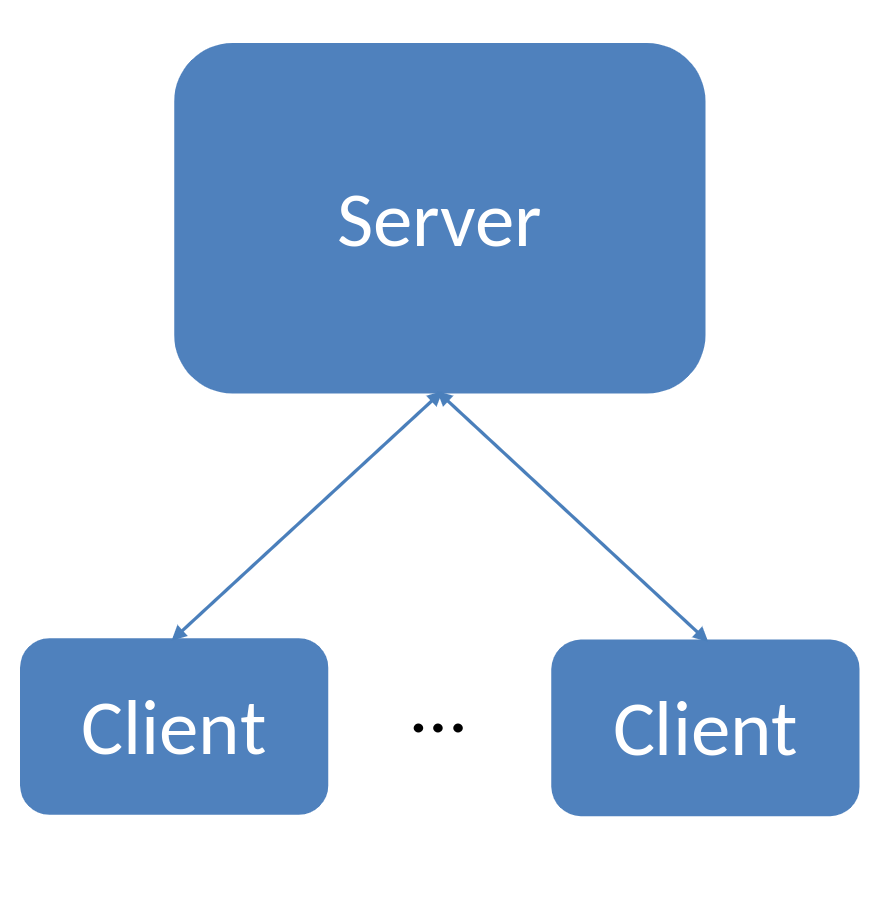

Client-Server Architecture#

Client-server architecture is a computing model that divides the functionality of a software application into two distinct components: the client and the server. This separation allows for efficient processing, improved scalability, and centralized management of data. Here are key aspects of client-server architecture:

Fig. 52 Client Server flow diagram#

Separation of User Interface and Data Processing:

In client-server architecture, the user interface (client) is separated from the data processing and storage (server). The client is responsible for presenting information to the user and handling user inputs, while the server manages the business logic, data processing, and storage.

Communication Between Client and Server:

The client sends requests to the server, requesting specific actions or data. The server processes these requests, executes the necessary operations, interacts with the database (if applicable), and returns the results to the client.

Client Responsibilities:

The client is focused on providing a user-friendly interface and handling user interactions. It may also perform some local processing, such as input validation or basic computations, before sending requests to the server.

Server Responsibilities:

The server hosts the application’s core logic, handling complex computations, data processing, and storage operations. It interacts with databases or other data storage systems to retrieve or update information based on client requests.

Communication Protocols:

Communication between the client and server typically relies on standardized protocols, such as HTTP, HTTPS, or WebSocket, facilitating seamless data exchange. These protocols ensure that the client and server can understand and interpret each other’s messages.

Distributed Processing:

Client-server architecture is well-suited for distributed processing, where tasks are divided between multiple servers to improve efficiency and performance. This enables applications to scale horizontally by adding more servers to distribute the workload.

Scalability:

The separation of concerns in client-server architecture makes it easier to scale the system. Scalability can be achieved by adding more clients, servers, or both, allowing the system to handle increased user load or data volume.

Centralized Data Management:

Data is typically stored centrally on the server, ensuring consistency and ease of management. Centralized data management simplifies tasks such as backups, updates, and security measures.

Security Considerations:

Security measures are often implemented on both the client and server sides to protect against unauthorized access and ensure the integrity of data during communication.

Examples of Usage:

Client-server architecture is commonly employed in web applications, where the web browser (client) interacts with a web server to request and display web pages. It is also used in various enterprise applications, databases, and distributed systems where the separation of concerns and scalability are essential.

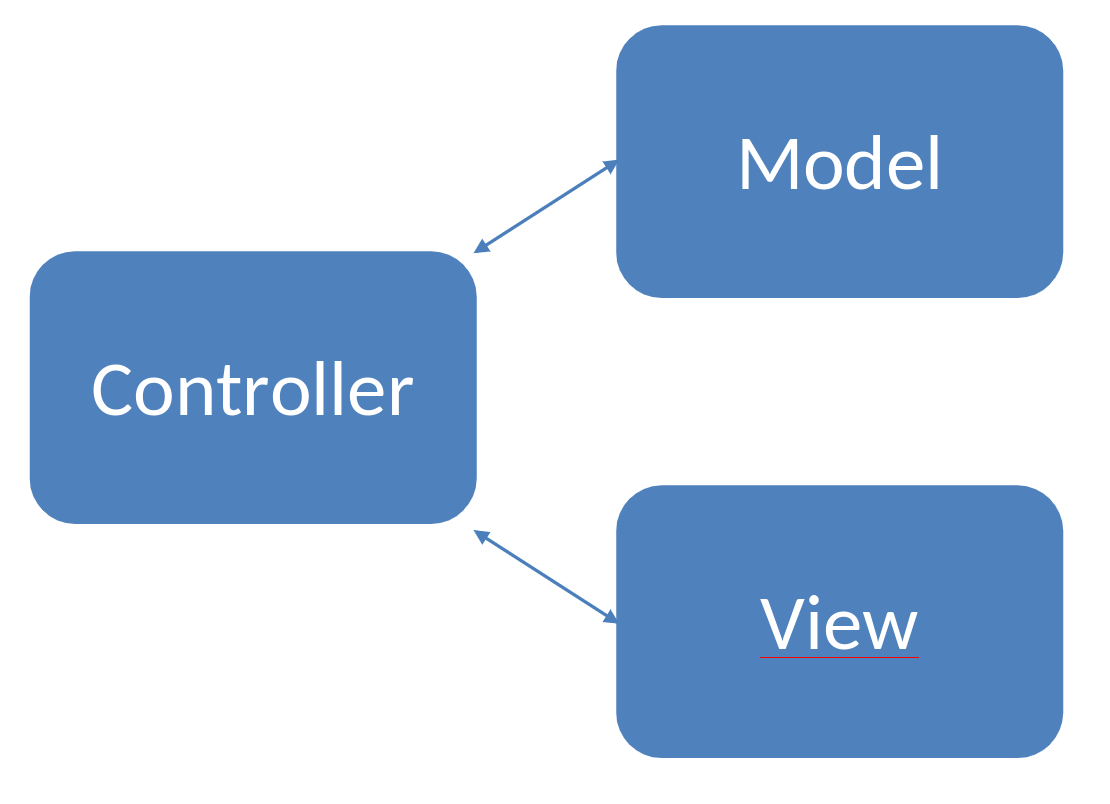

The Model-View_Controller (MVC)#

The Model-View-Controller (MVC) architectural pattern is a widely used design pattern in software development that helps in organizing and structuring code for better maintainability and scalability. It divides an application into three interconnected components, each responsible for a specific aspect of the application:

Fig. 53 Model View Controller#

Model (Data and Business Logic):

The model represents the application’s data and business logic. It encapsulates the data structure, storage, and manipulation, as well as the rules and algorithms that define the application’s behavior. By isolating data-related operations in the model, developers can make changes to the data structure or storage without affecting the user interface or the input handling logic. This promotes flexibility and ease of maintenance.

View (User Interface):

The view is responsible for presenting the data to the user and displaying the user interface. It receives information from the model and presents it in a way that is understandable and visually appealing to the user. Separating the view from the model ensures that changes in the user interface (UI) do not directly impact the underlying data or business logic. This separation allows for the development of multiple views for the same data, supporting different presentation formats or device-specific interfaces.

Controller (Handles User Input and Manages Interactions):

The controller acts as an intermediary between the model and the view. It receives user input from the UI, processes it, and updates the model accordingly. Additionally, the controller listens for changes in the model and updates the view to reflect any modifications in the underlying data. By isolating user input handling and interaction management in the controller, the model and view components remain independent. This separation allows for the reuse of controllers with different views or models, contributing to modularity and code reusability.

Benefits of MVC:#

Code Organization:

The MVC pattern provides a clear and structured organization of code, making it easier for developers to understand and maintain the application.

Modularity:

Each component (model, view, and controller) operates independently, promoting modularity. Changes in one component have minimal impact on the others, facilitating easier updates and modifications.

Flexibility:

The separation of concerns in MVC allows for flexibility in making changes to one component without affecting the others. This adaptability is crucial for evolving and scaling applications over time.

Collaboration:

MVC supports collaborative development as different teams or developers can work on different components simultaneously, reducing conflicts and improving productivity.

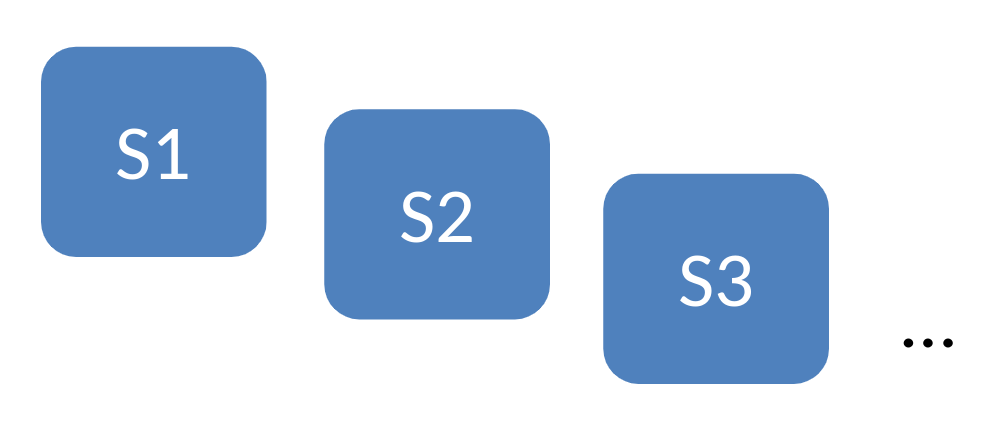

Microservices#

Microservices architecture is a modern approach to designing and building software systems, emphasizing the decomposition of a monolithic application into a collection of small, independent, and loosely coupled services. This architectural style has gained popularity due to its ability to address various challenges associated with traditional monolithic architectures.

Fig. 54 Microservices#

Key Characteristics of Microservices Architecture:

Decomposition into Small Services: Microservices architecture breaks down a complex system into smaller, manageable services, each focusing on a specific business capability. These services are independent entities that communicate with each other through well-defined APIs.

Loose Coupling: Services in a microservices architecture are loosely coupled, meaning that changes to one service do not significantly impact others. This independence allows for easier maintenance, updates, and modifications without affecting the entire system.

Independence and Autonomy: Each microservice is an autonomous unit with its own database, logic, and user interface if needed. This autonomy enables development teams to work on and deploy individual services independently, fostering faster release cycles.

Modularity: Microservices promote modularity by dividing a large system into smaller, self-contained modules. This makes it easier to understand, develop, test, deploy, and scale specific functionalities independently, promoting a more maintainable and scalable codebase.

Flexibility and Scalability: Microservices architecture provides flexibility in technology choices for each service, allowing developers to choose the most suitable technology stack for a specific task. This flexibility also enables horizontal scaling, where individual services can be scaled independently based on demand.

Fault Isolation: The isolation of services ensures that if one service fails, it does not necessarily lead to the failure of the entire system. This enhances the system’s fault tolerance and makes it more resilient.

Ease of Deployment and Continuous Delivery: Microservices architecture facilitates continuous integration and continuous delivery (CI/CD) practices. Smaller, independent services can be deployed more frequently, reducing the time between development and production releases.

Improved Maintenance and Upgrades: Since each service is independent, maintaining and upgrading the system becomes more manageable. Developers can focus on specific services without affecting the entire application, making it easier to address evolving requirements.

Evolvability: Microservices are well-suited for projects with evolving requirements. The modular nature of the architecture allows teams to adapt and change specific services without disrupting the entire system.

Despite these advantages, it’s important to note that implementing a microservices architecture also introduces challenges such as increased complexity in managing distributed systems, communication overhead, and potential issues with data consistency. Organizations need to carefully consider the trade-offs and suitability for their specific use cases before adopting this architectural style.

Layered Architecture#

Layered architecture is a fundamental design paradigm that systematically structures a software system into distinct horizontal layers, with each layer dedicated to executing specific functions. This architectural approach arranges these layers in a hierarchical manner, resembling a stack, where each layer interacts exclusively with the one directly above or below it. This strict layer-to-layer communication fosters a modular and organized environment, facilitating a more efficient and scalable software development process.

Fig. 55 Layered Architecture#

The primary advantage of a layered architecture lies in its modular and structured nature. By compartmentalizing functionalities into discrete layers, developers can focus on specific aspects of the system without being overwhelmed by the entire complexity. This separation of concerns not only simplifies the development process but also enhances the system’s maintainability and comprehensibility.

Each layer within the architecture is designed to handle a specific set of responsibilities, contributing to the overall functionality of the system. This delineation of tasks allows for a more straightforward identification and resolution of issues within individual layers, streamlining the debugging and maintenance processes. Moreover, the well-defined interfaces between layers promote a standardized communication protocol, minimizing dependencies and potential conflicts between different parts of the system.

Another key advantage of layered architecture is the promotion of reusability. Since each layer encapsulates a distinct set of functionalities, developers can reuse these modular components across different projects or within the same project, thereby reducing redundancy and saving valuable development time. This reusability not only accelerates the development process but also ensures consistency and reliability in the implementation of common functionalities.

In summary, layered architecture provides a systematic and disciplined approach to software development by organizing the system into hierarchical layers. This design principle enhances modularity, promotes separation of concerns, and facilitates reusability, ultimately leading to more scalable, maintainable, and efficient software systems.

Programming Styles#

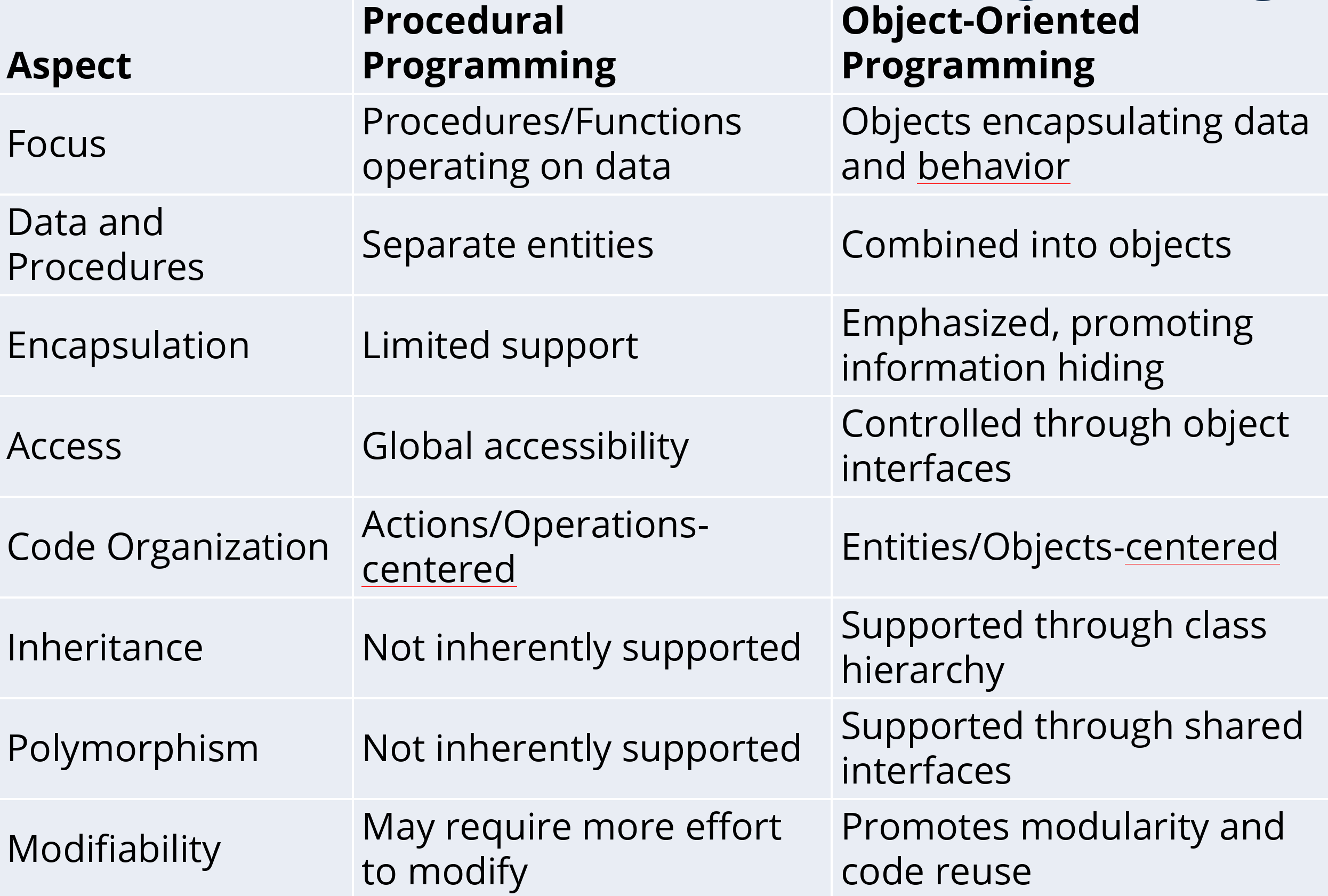

The selection of a programming paradigm hinges on the particular project’s requirements, complexity, and characteristics. Procedural programming may prove more fitting for smaller projects or scenarios that prioritize simplicity and direct data control. On the other hand, object-oriented programming is frequently preferred for larger, intricate systems where the emphasis lies on modularity, encapsulation, and code reuse. It is also feasible to incorporate both programming styles within a single project.

The following Table shows a direct comparison between Procedural and Object Oriented Programming.

Fig. 56 Programming Styles#

OOP Approach#

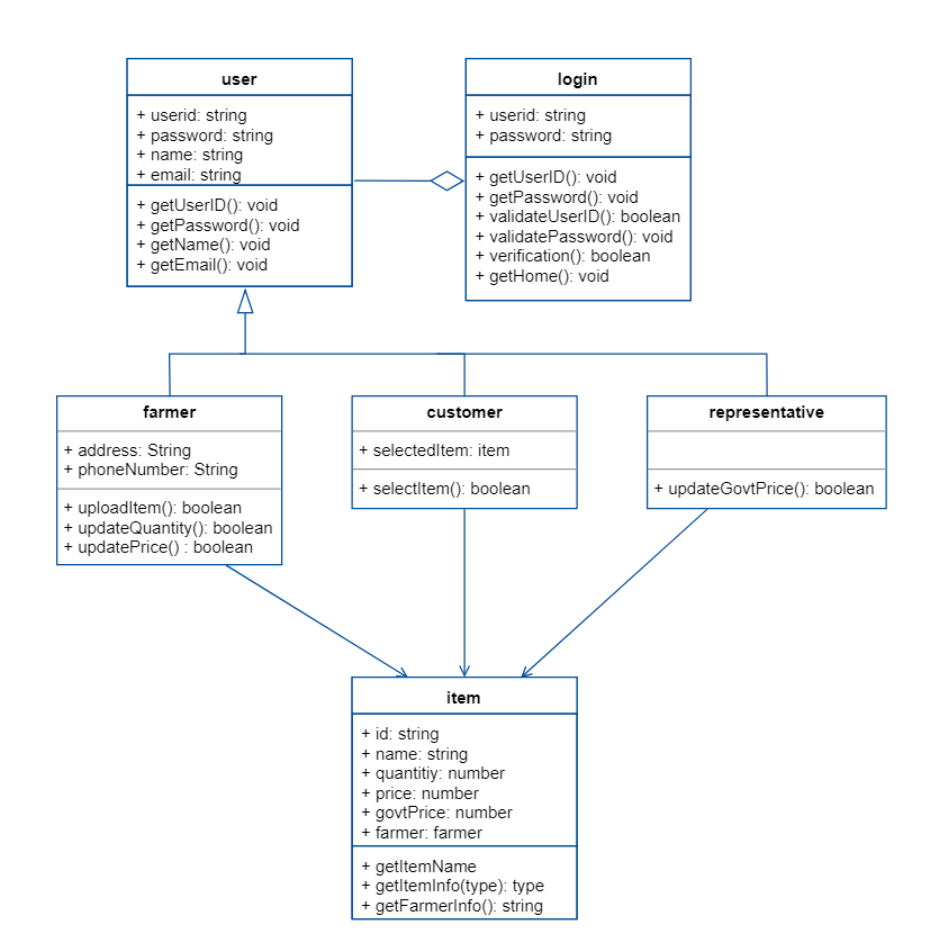

If you go for an OOP approach, you need to identify the relevant objects and classes, and their properties, behaviour and interactions.

The process is not always straightforward, and it requires a deep understanding of the domain and collaboration with stakeholders.

Essential to consider the context, project constraints, and the specific needs of the software system.

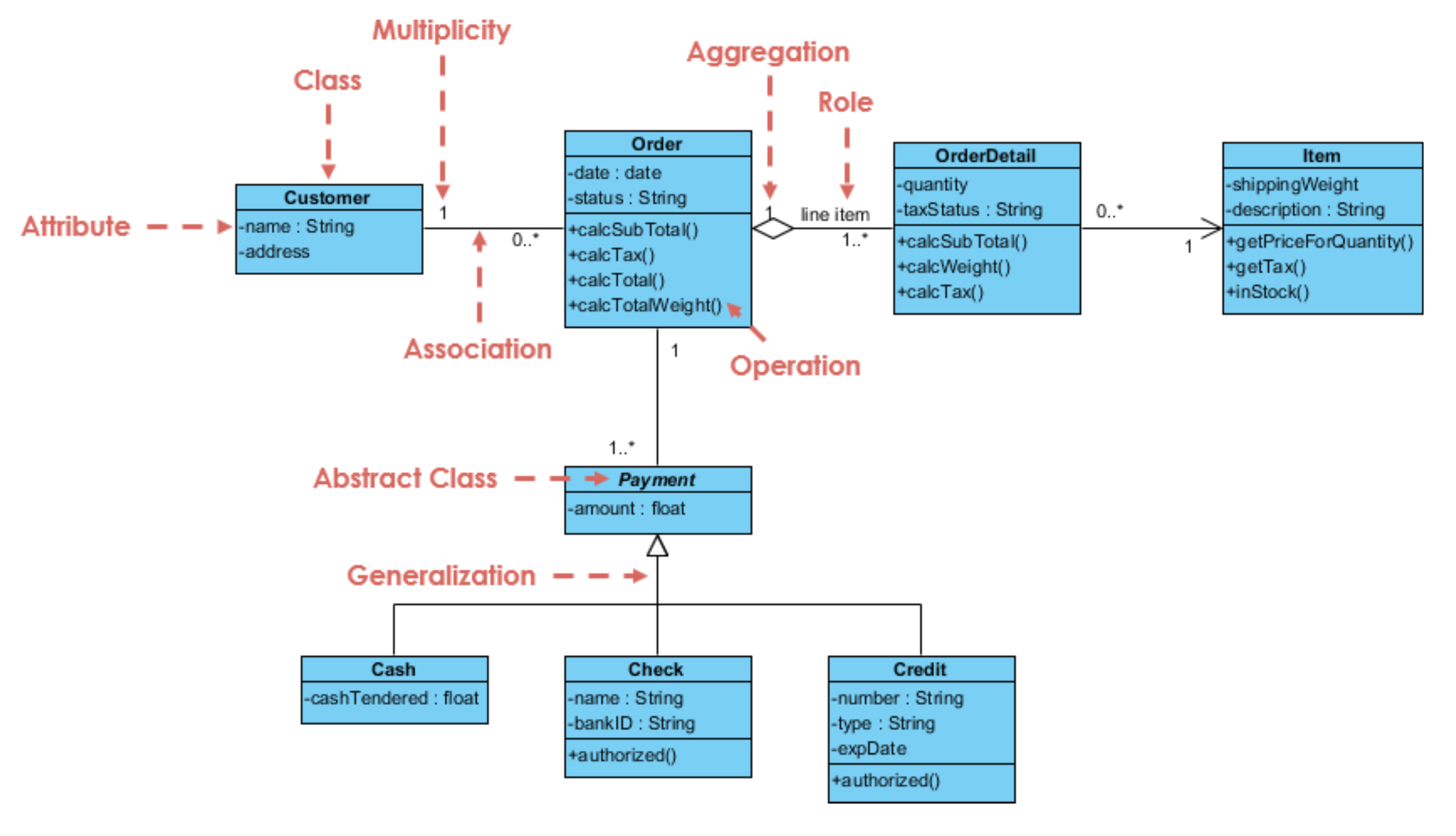

Utilize UML (Unified Modeling Language) class diagrams to depict the structure and interconnections among classes.

These diagrams provide a comprehensive view of classes, encompassing their attributes, methods, and the associations linking them. They offer a standardized and visual method for illustrating the static structure of a system.

Fig. 57 UML Class Diagram#

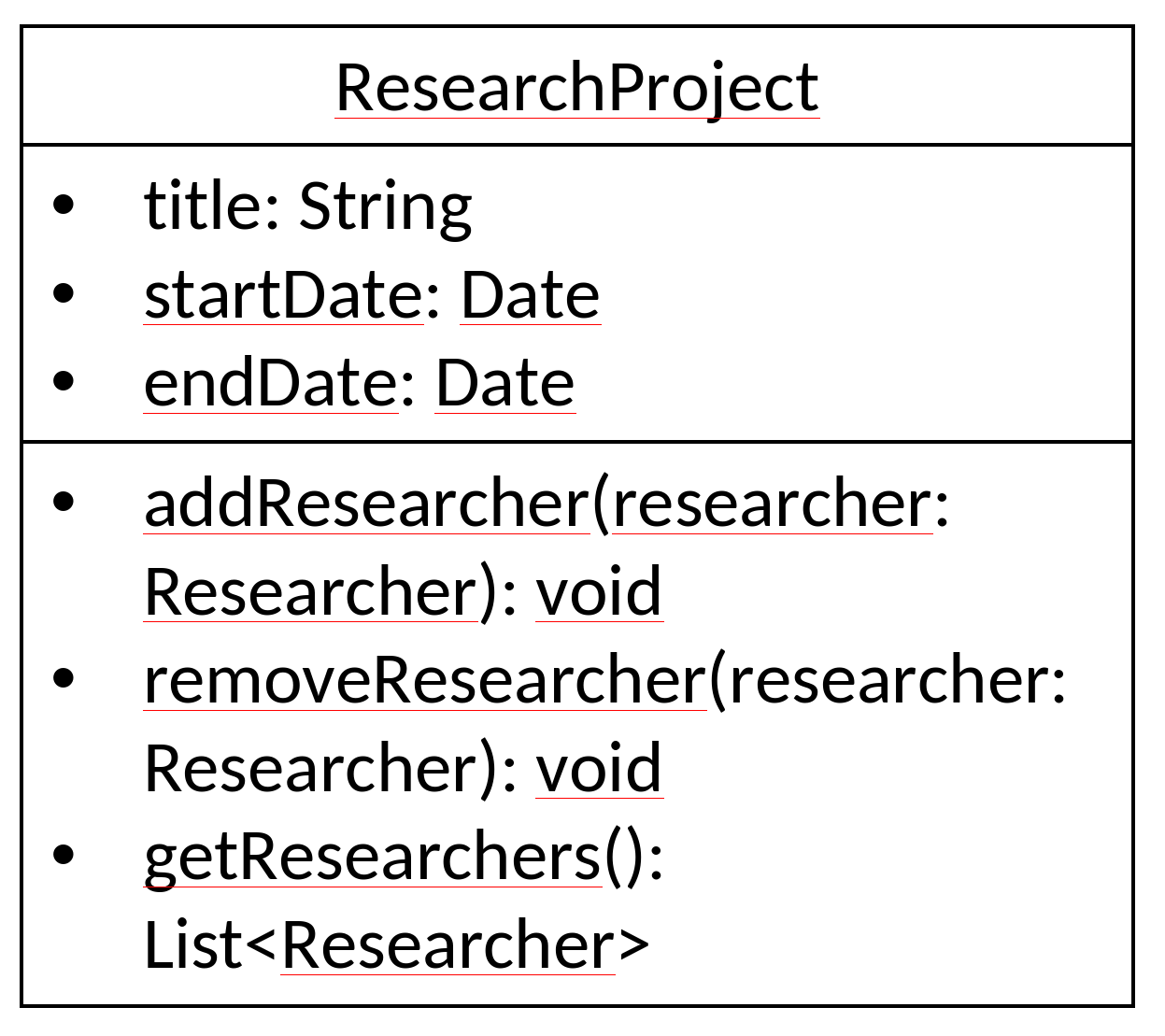

Classes#

Classes are represented as rectangles divided into three sections.

top section: class name

middle section: attributes (data members or variables)

bottom section: methods (operations or functions)

Fig. 58 Class Diagram#

Relationship between Classes#

In Object-Oriented Programming (OOP), class relationships play a pivotal role in organizing and modeling the structure of a software system. At the core of OOP is the concept of classes, which are blueprints for creating objects, encapsulating data, and defining behavior. Class relationships establish connections between these classes, facilitating the creation of complex, modular, and maintainable code.

One fundamental type of class relationship is inheritance, where a class (subclass or derived class) can inherit attributes and methods from another class (superclass or base class). This promotes code reuse, enhances extensibility, and fosters a hierarchical structure. Polymorphism is another crucial relationship, enabling objects of different classes to be treated interchangeably, enhancing flexibility and adaptability.

Additionally, OOP introduces associations, aggregations, and compositions to model more complex relationships. Associations represent connections between classes, aggregations depict a whole-part relationship with weaker coupling, and compositions signify a stronger bond where the existence of one class is dependent on another.

Effective use of class relationships in OOP allows developers to create modular and scalable systems. By carefully designing and managing these relationships, developers can achieve code that is not only robust but also adaptable to changing requirements, fostering the principles of encapsulation, abstraction, and code reusability.

Fig. 59 Class Relationships#

To find the required classes/objects in the requirements, you can follow these steps:#

Consider Functional Requirements: Examine the functional requirements and use cases in the requirements document. They often describe interactions and collaborations between different classes or objects.

Identify Key Concepts: Look for domain-specific or problem-specific concepts mentioned in the requirements. These concepts often correspond to classes or objects in the software system.

Analyze the Verbs and Nouns: Review the requirements document or statement and identify the verbs and nouns used. Verbs often indicate actions or behaviors, while nouns typically represent entities or objects in the system.

Extract Entities and Relationships: Identify the entities or objects described in the requirements and the relationships between them. Look for phrases or descriptions that imply associations, dependencies, or interactions between entities.

Look for System Boundaries: Determine the boundaries of the system as described in the requirements. This can help identify the main components or objects in the system.

Also important:

Collaborate with Stakeholders: Engage in discussions with stakeholders, including domain experts, users, and developers. Their insights and perspectives can help identify the relevant classes or objects in the requirements.

Iterate and Refine: Continuously refine and iterate your understanding of the requirements. Capture any uncertainties or questions you may have and seek clarification from stakeholders to ensure a comprehensive understanding.

For more advanced design patterns (become more important with larger systems) see, e.g.:

“Gang of Four” Design Patterns Reference GoF design patterns in Python