Forking on Github#

Since some of the readers are not University of Potsdam members, and thereby have no UoP Gitlab account we have included the original Github instructions used in the book by Irving et all.

Using Other People’s Work - GITHUB version#

So far we have used Git to manage individual work, but it really comes into its own when we are working with other people. We can do this in two ways:

Everyone has read and write access to a single shared repository.

Everyone can read from the project’s main repository, but only a few people can commit changes to it. The project’s other contributors fork the main repository to create one that they own, do their work in that, and then submit their changes to the main repository.

The first approach works well for teams of up to half a dozen people

who are all comfortable using Git, but if the project is larger,

or if contributors are worried that they might make a mess in the master branch, the second approach is safer.

Git itself doesn’t have any notion of a “main repository”,

but \gref{forges}{forge} like Github, Gitlab, Bitbucket or selfhosted solutions like Gitea all encourage people to use Git in ways that effectively create one.

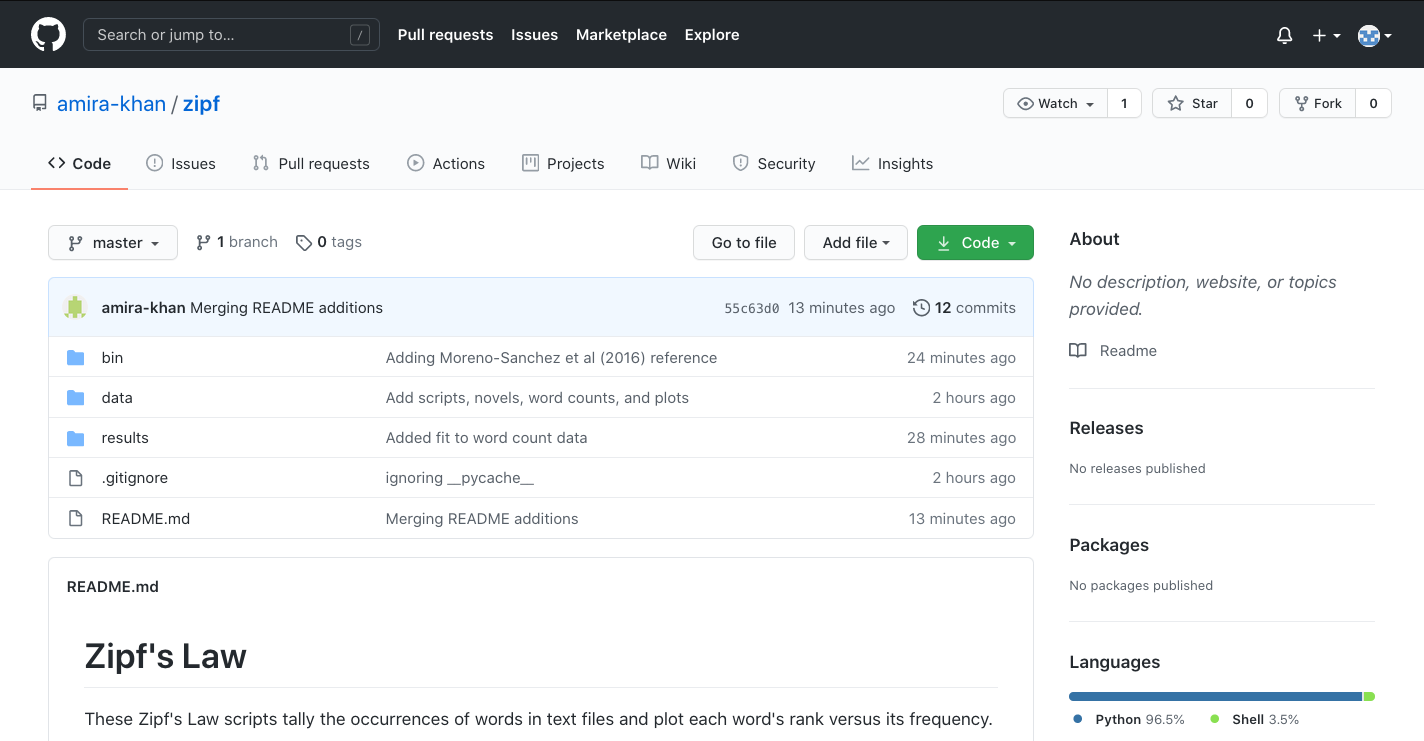

Suppose, for example, that Sami wants to contribute to the Zipf’s Law code that

Amira is hosting on GitHub at https://github.com/amira-khan/zipf.

Sami can go to that URL and click on the “Fork” button in the upper right corner

(Figure: fork button).

GitHub immediately creates a copy of Amira’s repository within Sami’s account on GitHub’s own servers.

Fig. 22 Git Fork button#

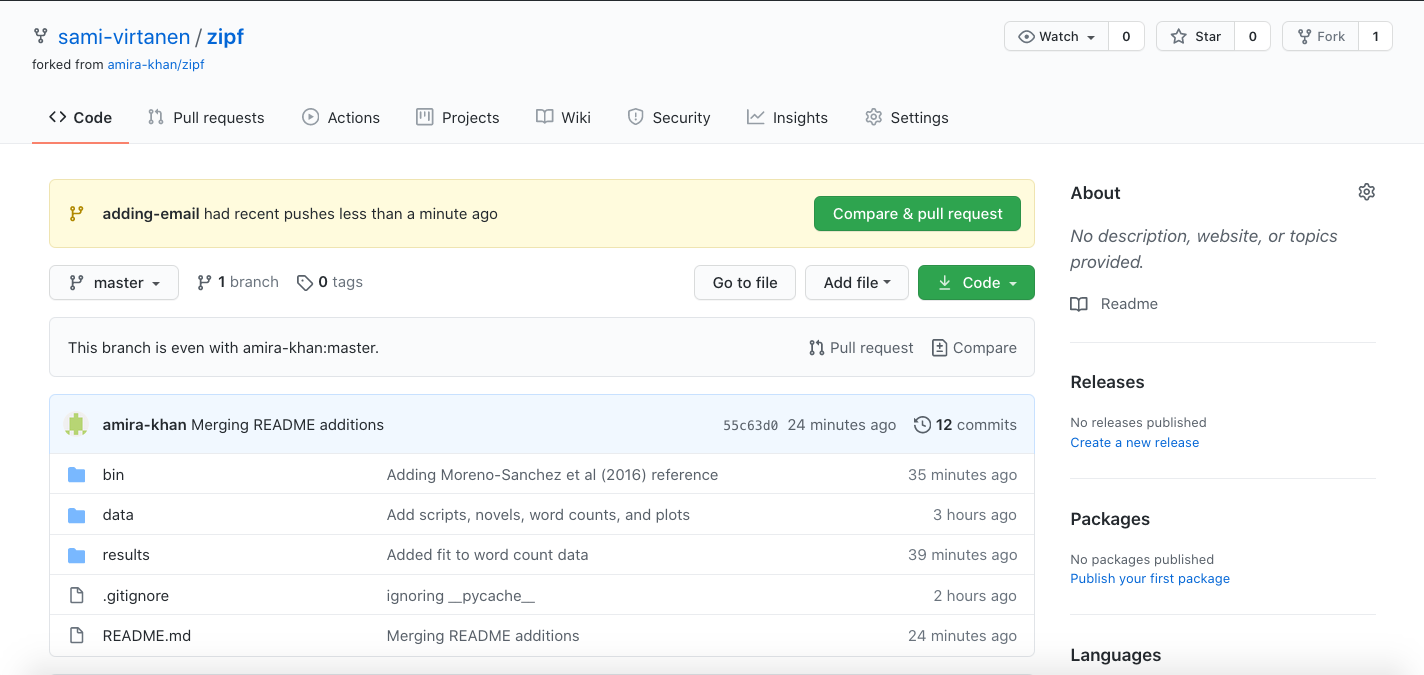

When the command completes, the setup on GitHub now looks like Figure: after fork.Nothing has happened yet on Sami’s own machine: the new repository exists only on GitHub. When Sami explores its history, they see that it contains all of the changes Amira made.

Fig. 23 Git: After Fork#

A copy of a repository is called a clone In order to start working on the project, Sami needs a clone of their repository (not Amira’s) on their own computer. We will modify Sami’s prompt to include their desktop user ID (sami

and working directory (initially ~) to make it easier to follow what’s happening:

sami:~ $ git clone https://github.com/sami-virtanen/zipf.git

Cloning into 'zipf'...

remote: Enumerating objects: 64, done.

remote: Counting objects: 100% (64/64), done.

remote: Compressing objects: 100% (43/43), done.

remote: Total 64 (delta 20), reused 63 (delta 19), pack-reused 0

Receiving objects: 100% (64/64), 2.20 MiB | 2.66 MiB/s, done.

Resolving deltas: 100% (20/20), done.

This command creates a new directory with the same name as the project,

i.e., zipf. When Sami goes into this directory and runs ls and git log,

they see that all of the project’s files and history are there:

sami:~ $ cd zipf

sami:~/zipf $ ls

README.md bin data results

sami:~/zipf $ git log --oneline -n 4

55c63d0 (HEAD -> master, origin/master, origin/HEAD)

Merging README additions

45a576b Added contributor list

a0b88e5 Added repository overview

232b564 Initial commit of README file

Sami also sees that Git has automatically created a remote for their repository that points back at their repository on GitHub:

sami:~/zipf $ git remote -v

origin https://github.com/sami-virtanen/zipf.git (fetch)

origin https://github.com/sami-virtanen/zipf.git (push)

Sami can pull changes from their fork and push work back there, but needs to do one more thing before getting the changes from Amira’s repository:

sami:~/zipf $ git remote add upstream

https://github.com/amira-khan/zipf.git

sami:~/zipf $ git remote -v

origin https://github.com/sami-virtanen/zipf.git (fetch)

origin https://github.com/sami-virtanen/zipf.git (push)

upstream https://github.com/amira-khan/zipf.git (fetch)

upstream https://github.com/amira-khan/zipf.git (push)

Sami has called their new remote upstream because it points at the repository

from which theirs is derived. They could use any name, but upstream is a nearly universal convention.

With this remote in place, Sami is finally set up. Suppose, for example,

that Amira has modified the project’s README.md file to add Sami as a contributor. (Again, we show Amira’s user ID and working directory in her prompt to make it clear who’s doing what):

# Zipf's Law

These Zipf's Law scripts tally the occurrences of words in text

files and plot each word's rank versus its frequency.

## Contributors

- Amira Khan <amira@zipf.org>

- Sami Virtanen

Amira commits her changes and pushes them to her repository on GitHub:

amira:~/zipf $ git commit -a -m "Adding Sami as a contributor"

[master 35fca86] Adding Sami as a contributor

1 file changed, 1 insertion(+)

amira:~/zipf $ git push origin master

Enumerating objects: 5, done.

Counting objects: 100% (5/5), done.

Delta compression using up to 4 threads

Compressing objects: 100% (3/3), done.

Writing objects: 100% (3/3), 315 bytes | 315.00 KiB/s, done.

Total 3 (delta 2), reused 0 (delta 0), pack-reused 0

remote: Resolving deltas: 100% (2/2), completed with 2 local

objects.

To https://github.com/amira-khan/zipf.git

55c63d0..35fca86 master -> master

\newpage

Amira’s changes are now on her desktop and in her GitHub repository but not in either of Sami’s repositories (local or remote). Since Sami has created a remote that points at Amira’s GitHub repository, though, they can easily pull those changes to their desktop:

sami:~/zipf $ git pull upstream master

From https://github.com/amira-khan/zipf

* branch master -> FETCH_HEAD

* [new branch] master -> upstream/master

Updating 55c63d0..35fca86

Fast-forward

README.md | 1 +

1 file changed, 1 insertion(+)

Pulling from a repository owned by someone else is no different than pulling from a repository we own. In either case, Git merges the changes and asks us to resolve any conflicts that arise.

The only significant difference is that, as with git push and git pull,

we have to specify both a remote and a branch:

in this case, upstream and master.

Pull Requests#

Sami can now get Amira’s work, but how can Amira get Sami’s? She could create a remote that pointed at Sami’s repository on GitHub and periodically pull in Sami’s changes, but that would lead to chaos, since we could never be sure that everyone’s work was in any one place at the same time. Instead, almost everyone uses pull requests. They aren’t part of Git itself, but are supported by all major online forges.

A pull request is essentially a note saying, “Someone would like to merge branch A of repository B into branch X of repository Y.” The pull request does not contain the changes, but instead points at two particular branches. That way, the difference displayed is always up to date if either branch changes.

But a pull request can store more than just the source and destination branches: it can also store comments people have made about the proposed merge. Users can comment on the pull request as a whole, or on particular lines, and mark comments as out of date if the author of the pull request updates the code that the comment is attached to. Complex changes can go through several rounds of review and revision before being merged, which makes pull requests the review system we all wish journals actually had.

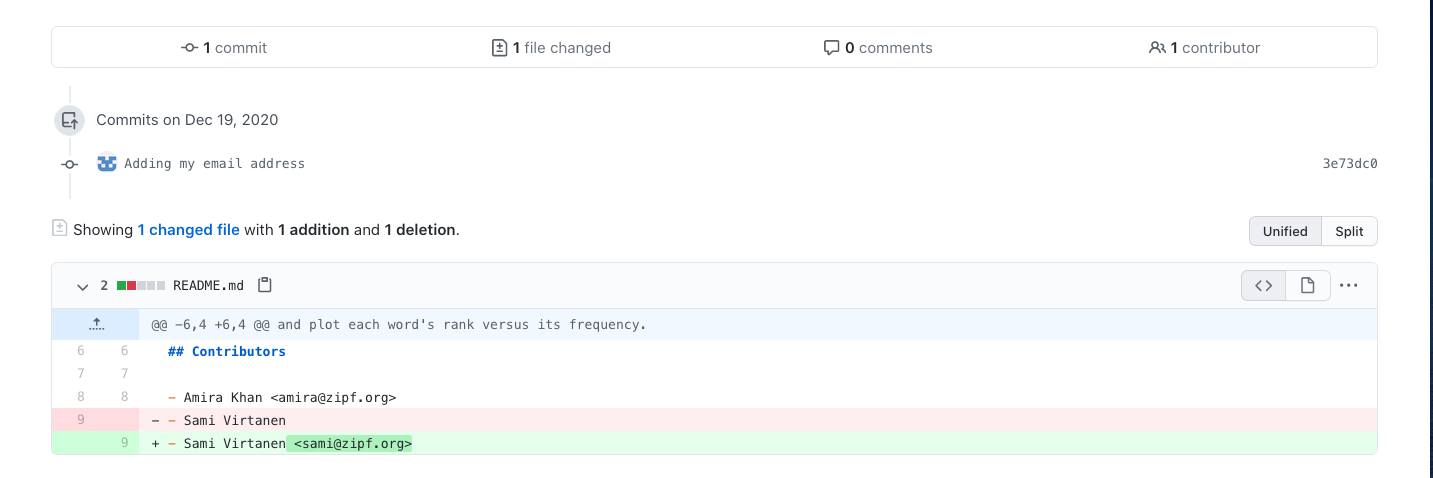

To see this in action, suppose Sami wants to add their email address to README.md. They create a new branch and switch to it:

sami:~/zipf $ git checkout -b adding-email

Switched to a new branch 'adding-email'

then make a change and commit it:

sami:~/zipf $ git commit -a -m "Adding my email address"

[adding-email 3e73dc0] Adding my email address

1 file changed, 1 insertion(+), 1 deletion(-)

sami:~/zipf $ git diff HEAD~1

diff --git a/README.md b/README.md

index e8281ee..e1bf630 100644

--- a/README.md

+++ b/README.md

@@ -6,4 +6,4 @@ and plot each word's rank versus its frequency.

## Contributors

- Amira Khan <amira@zipf.org>

-- Sami Virtanen

+- Sami Virtanen <sami@zipf.org>

Sami’s changes are only in their local repository. They cannot create a pull request until those changes are on GitHub, so they push their new branch to their repository on GitHub:

sami:~/zipf $ git push origin adding-email

Enumerating objects: 5, done.

Counting objects: 100% (5/5), done.

Delta compression using up to 4 threads

Compressing objects: 100% (3/3), done.

Writing objects: 100% (3/3), 315 bytes | 315.00 KiB/s, done.

Total 3 (delta 2), reused 0 (delta 0), pack-reused 0

remote: Resolving deltas: 100% (2/2), completed with 2 local

objects.

remote:

remote: Create a pull request for 'adding-email' on GitHub by

visiting:

https://github.com/sami-virtanen/zipf/pull/new/adding-email

remote:

To https://github.com/sami-virtanen/zipf.git

* [new branch] adding-email -> adding-email

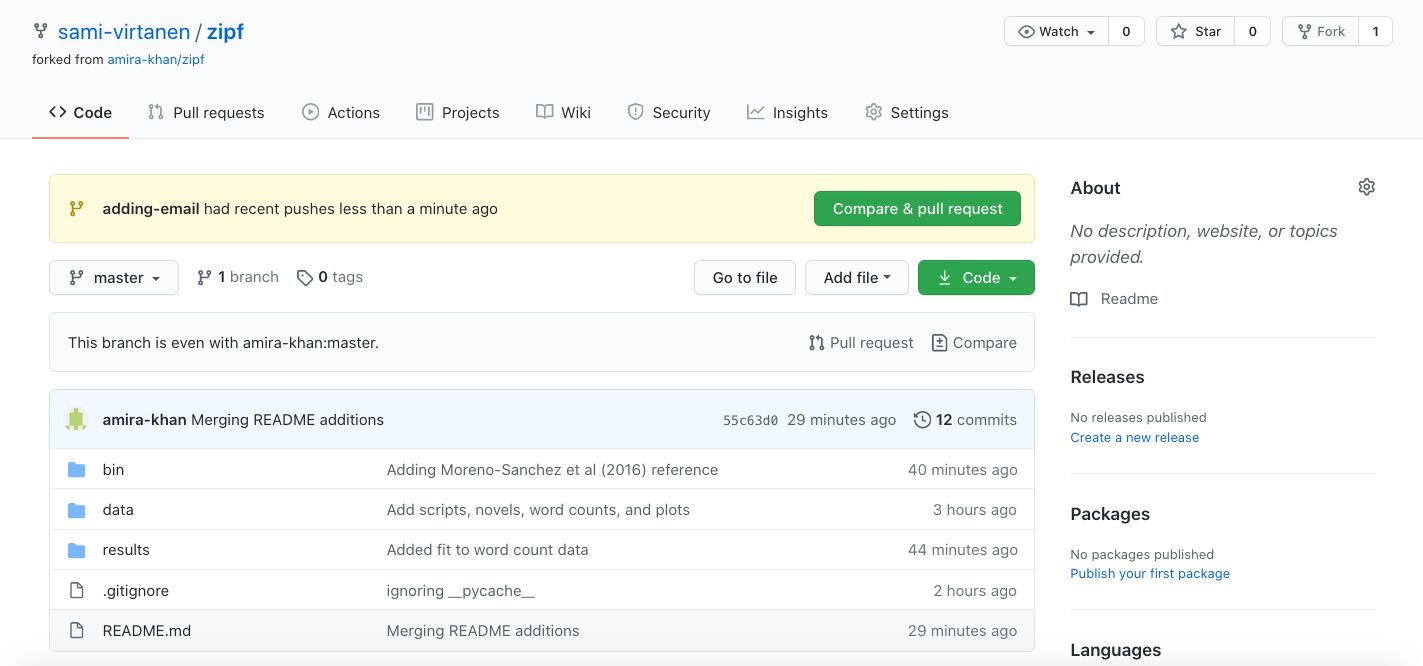

When Sami goes to their GitHub repository in the browser, GitHub notices that they have just pushed a new branch and asks them if they want to create a pull request (Figure: after push).

Fig. 24 Git after Push#

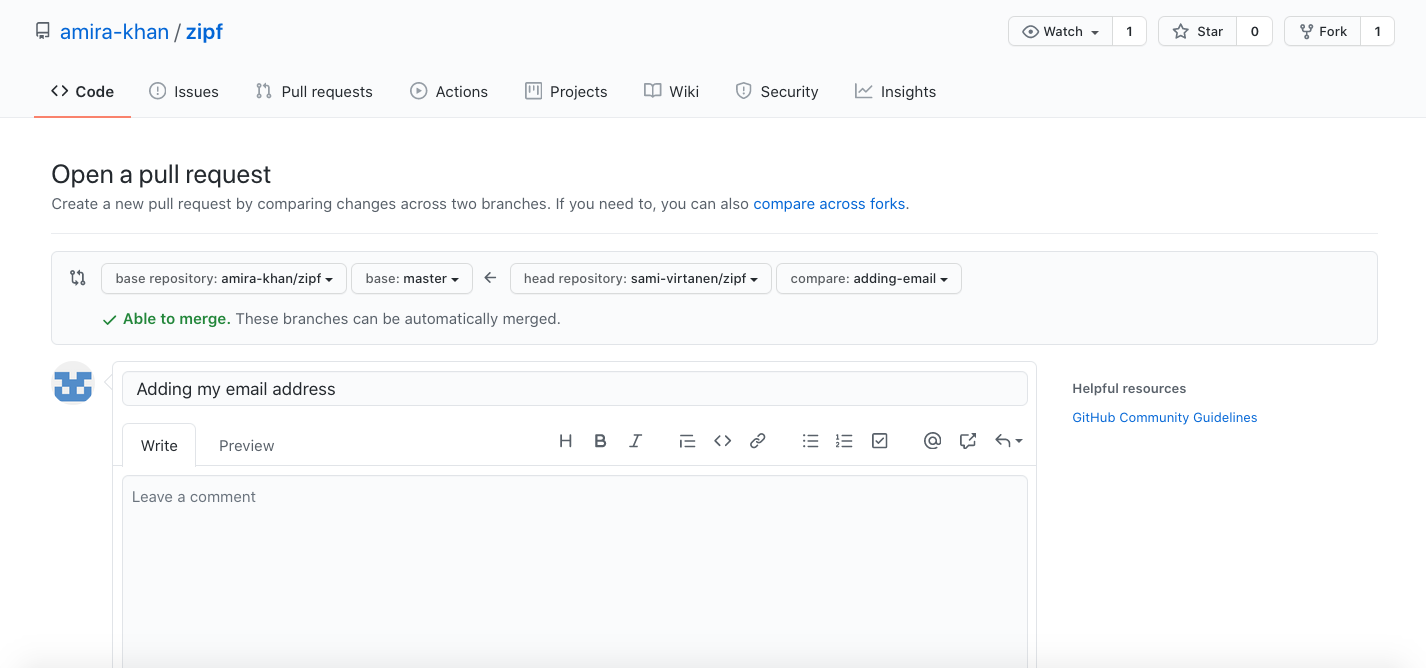

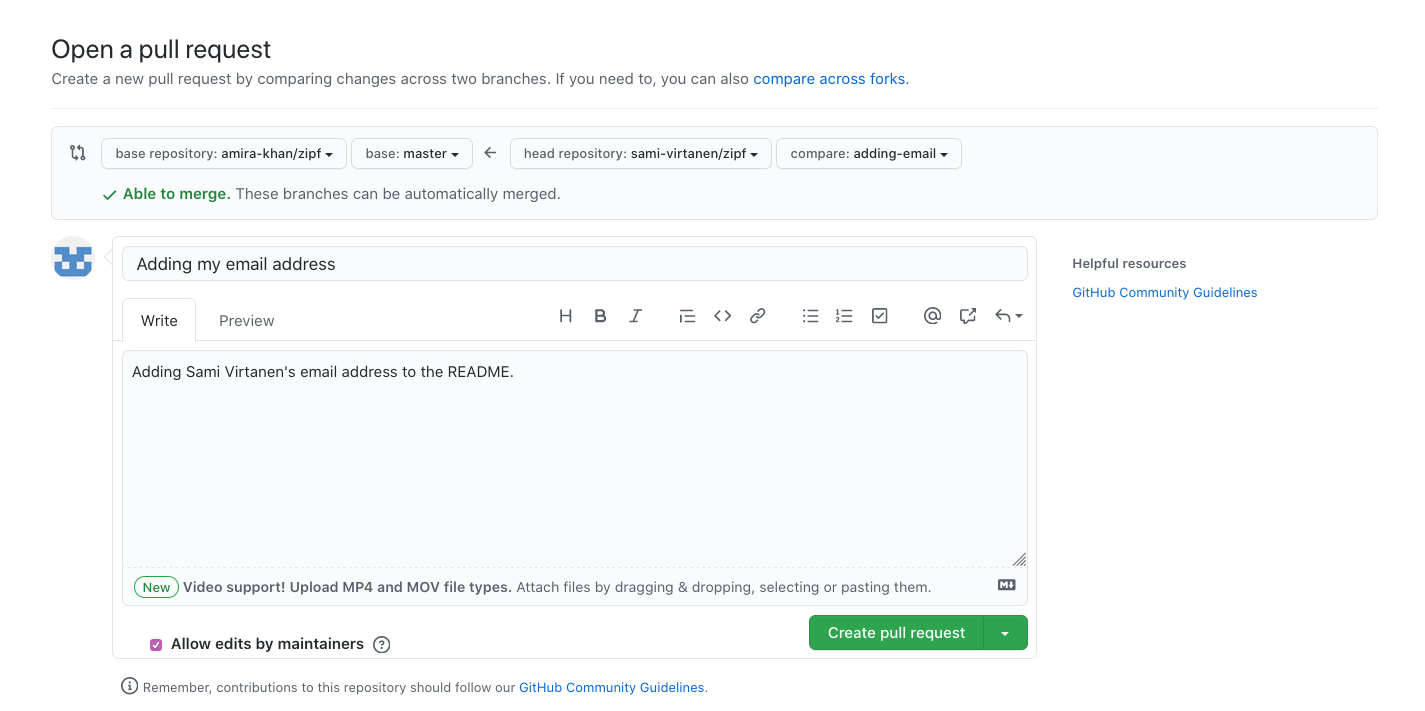

When Sami clicks on the button, GitHub displays a page showing the default source and destination of the pull request and a pair of editable boxes for the pull request’s title and a longer comment (Figure: pull request start).

Fig. 25 Start a pull request#

If they scroll down, Sami can see a summary of the changes that will be in the pull request (Figure: pull request summary).

Fig. 26 Git pull request summary#

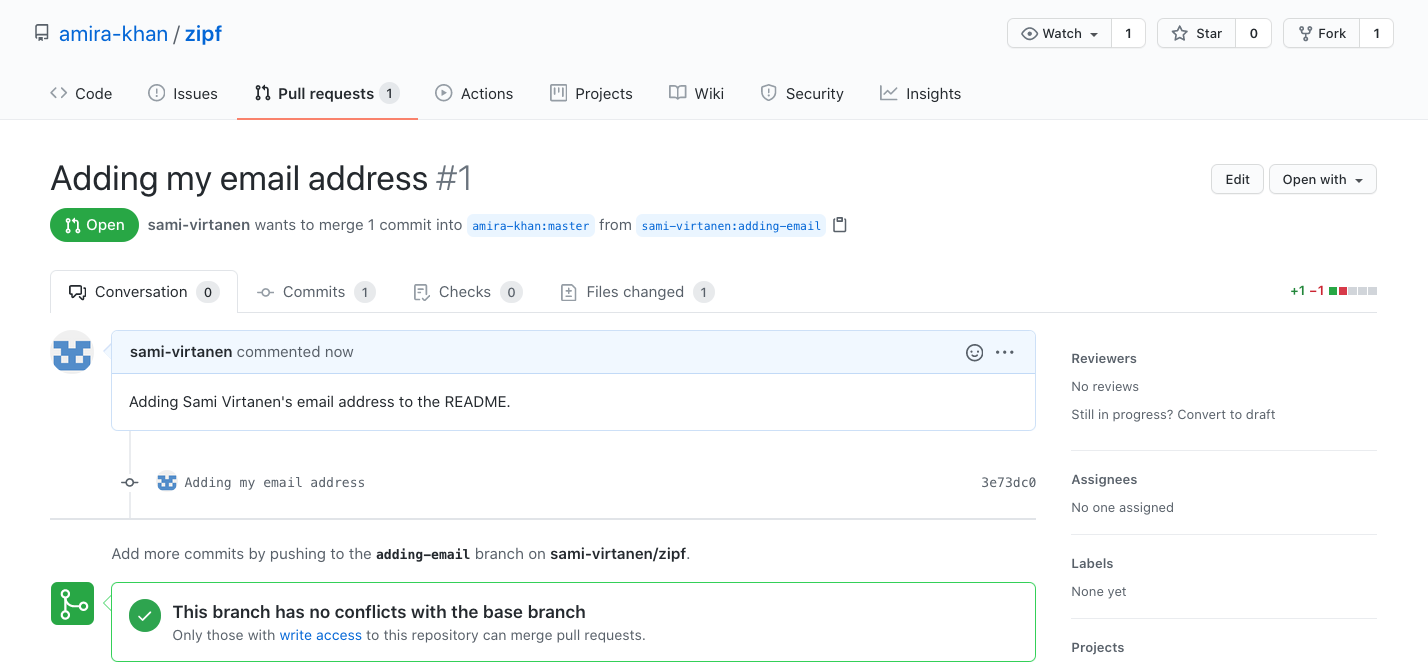

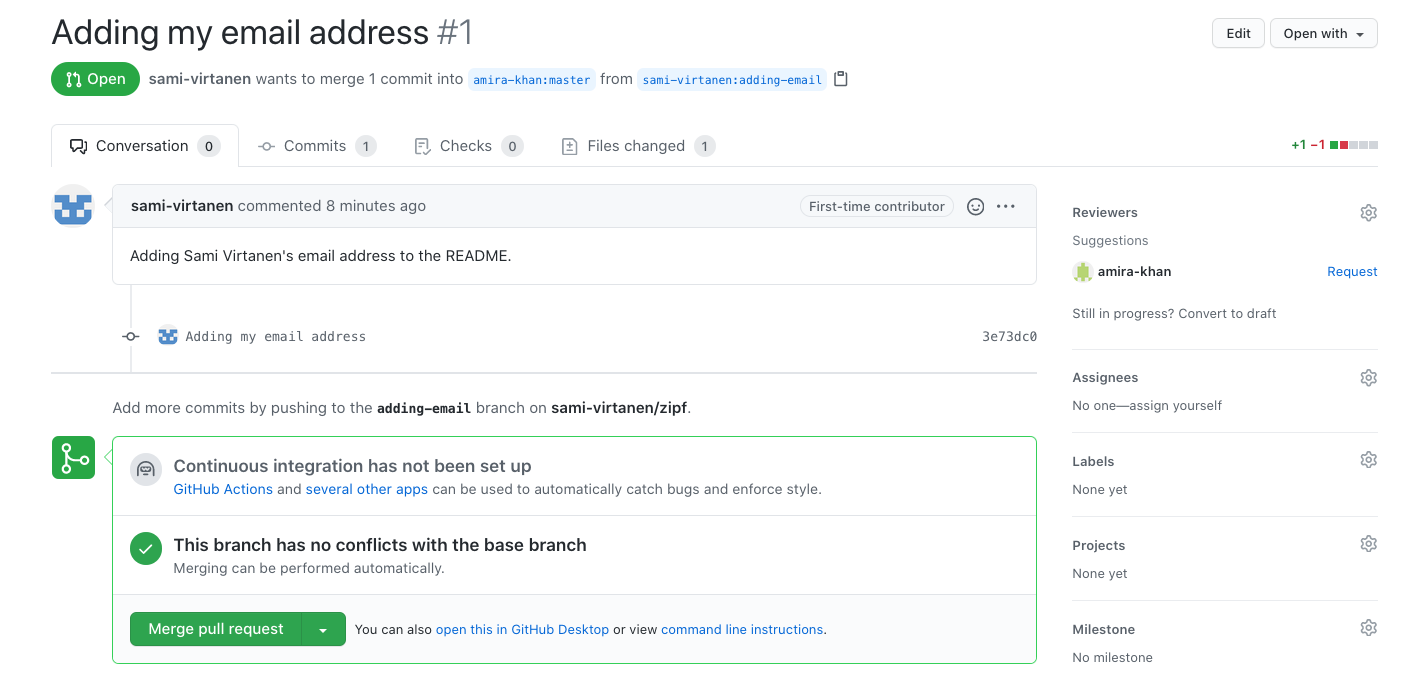

The top (title) box is autofilled with the previous commit message, so Sami adds an extended explanation to provide additional context before clicking on “Create Pull Request” (Figure: fill in pull request). When they do, GitHub displays a page showing the new pull request, which has a unique serial number (Figure :New pull request). Note that this pull request is displayed in Amira’s repository rather than Sami’s, since it is Amira’s repository that will be affected if the pull request is merged.

Fig. 27 Git Fill in pull request#

Fig. 28 Git new pull request#

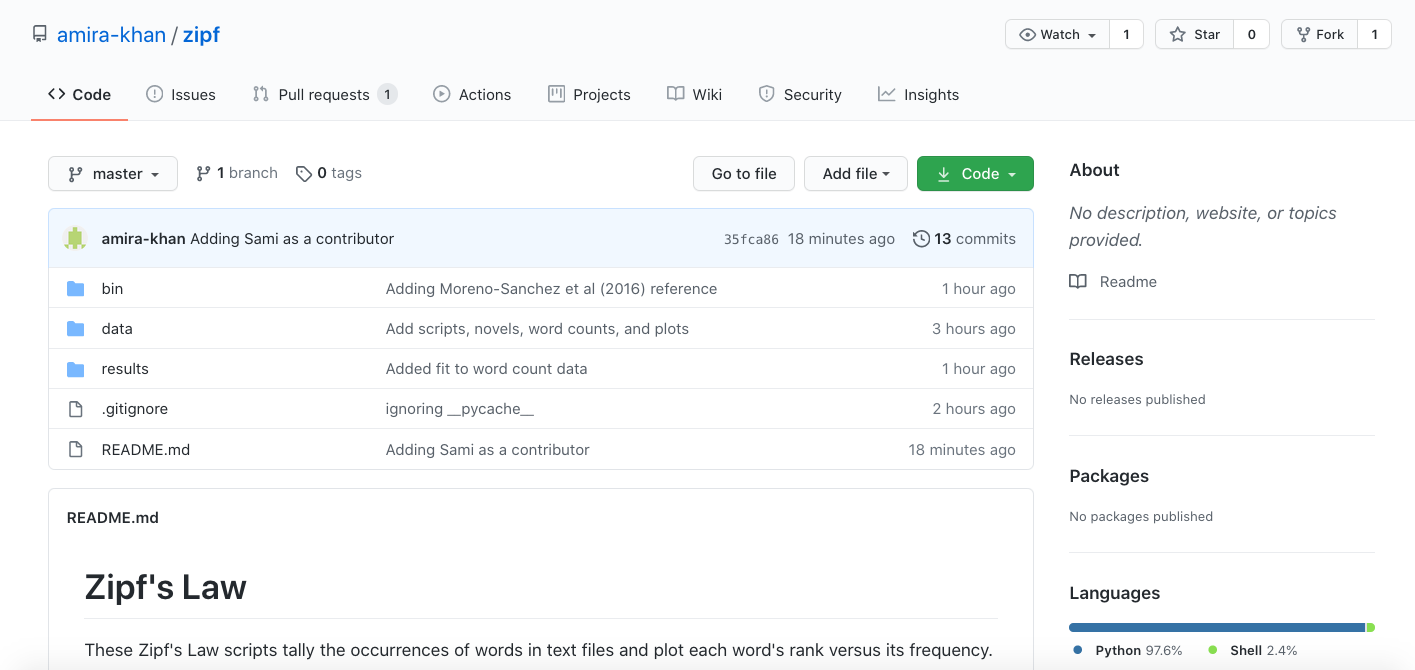

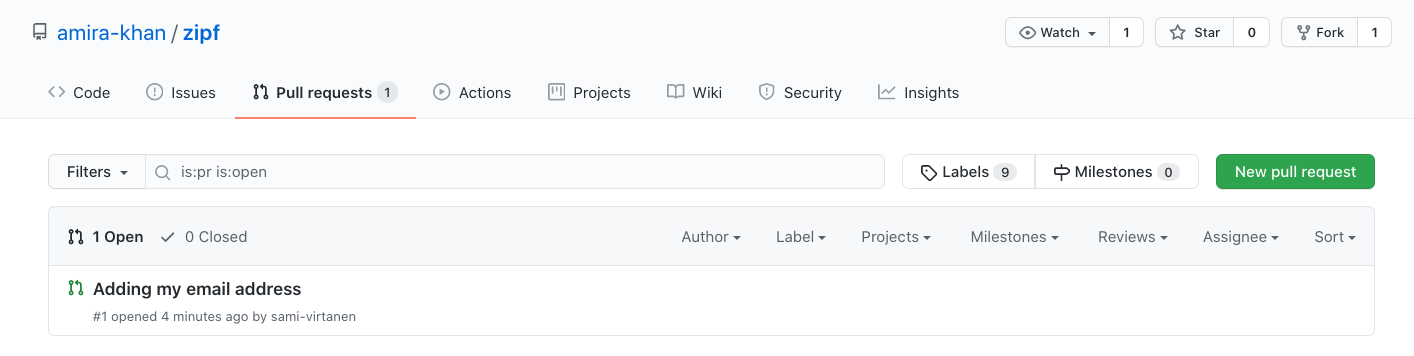

Amira’s repository now shows a new pull request (Figure: view Pull requests). Clicking on the “Pull requests” tab brings up a list of PRs (Figure: list pull requests) and clicking on the pull request link itself displays its details (Figure: pull request details). Sami and Amira can both see and interact with these pages, though only Amira has permission to merge.

Fig. 29 View pull request#

Fig. 30 Git pull request list#

Fig. 31 Git pull request details#

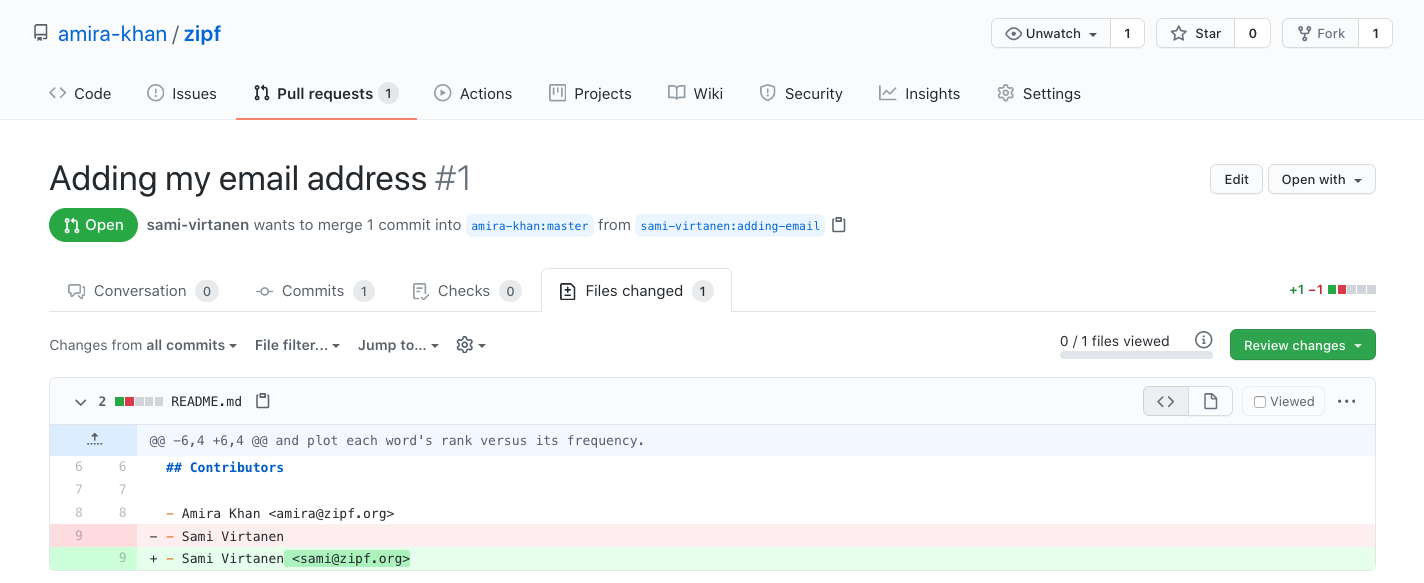

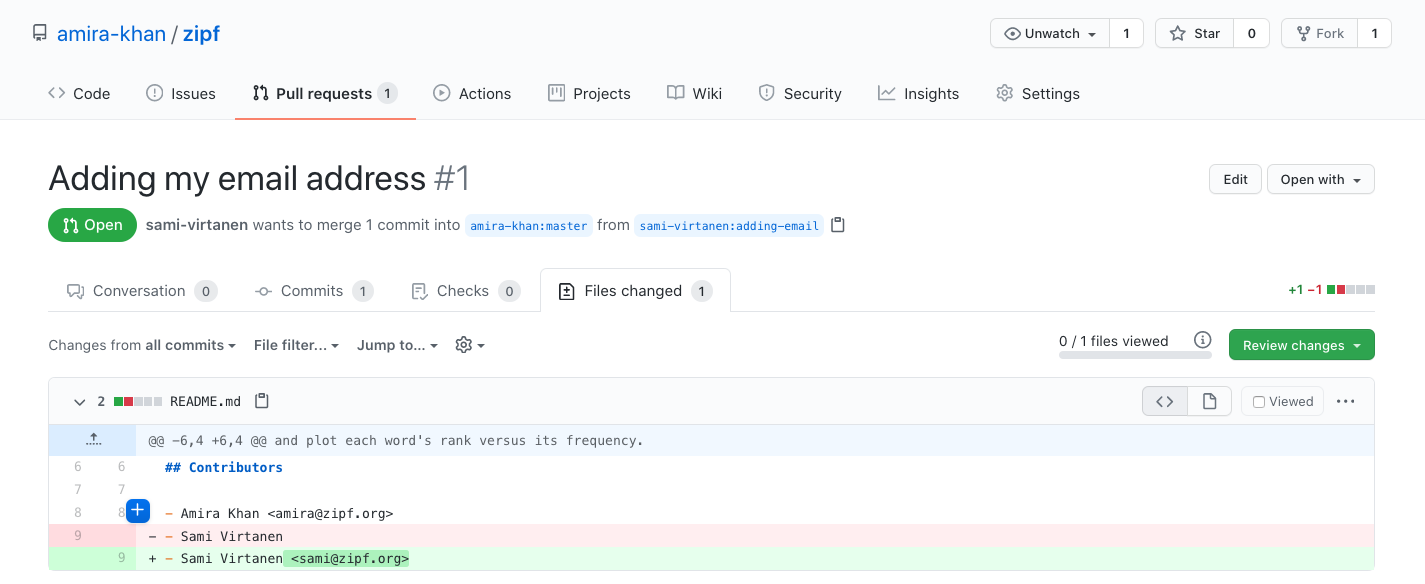

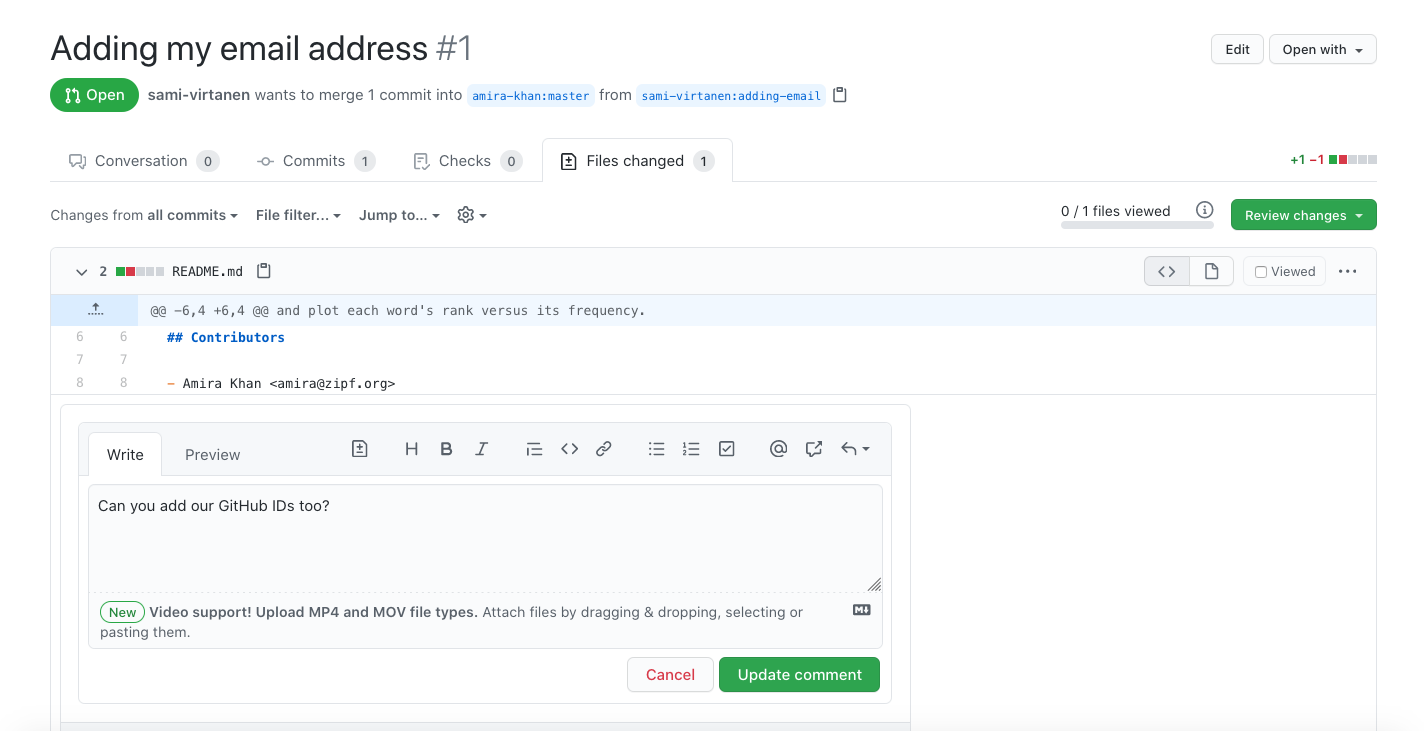

Since there are no conflicts,GitHub will let Amira merge the PR immediately using the “Merge pull request” button. She could also discard or reject it without merging using the “Close pull request” button. Instead, she clicks on the “Files changed” tab to see what Sami has changed (Figure: Pull request - request changes).

Fig. 32 Pull request changes#

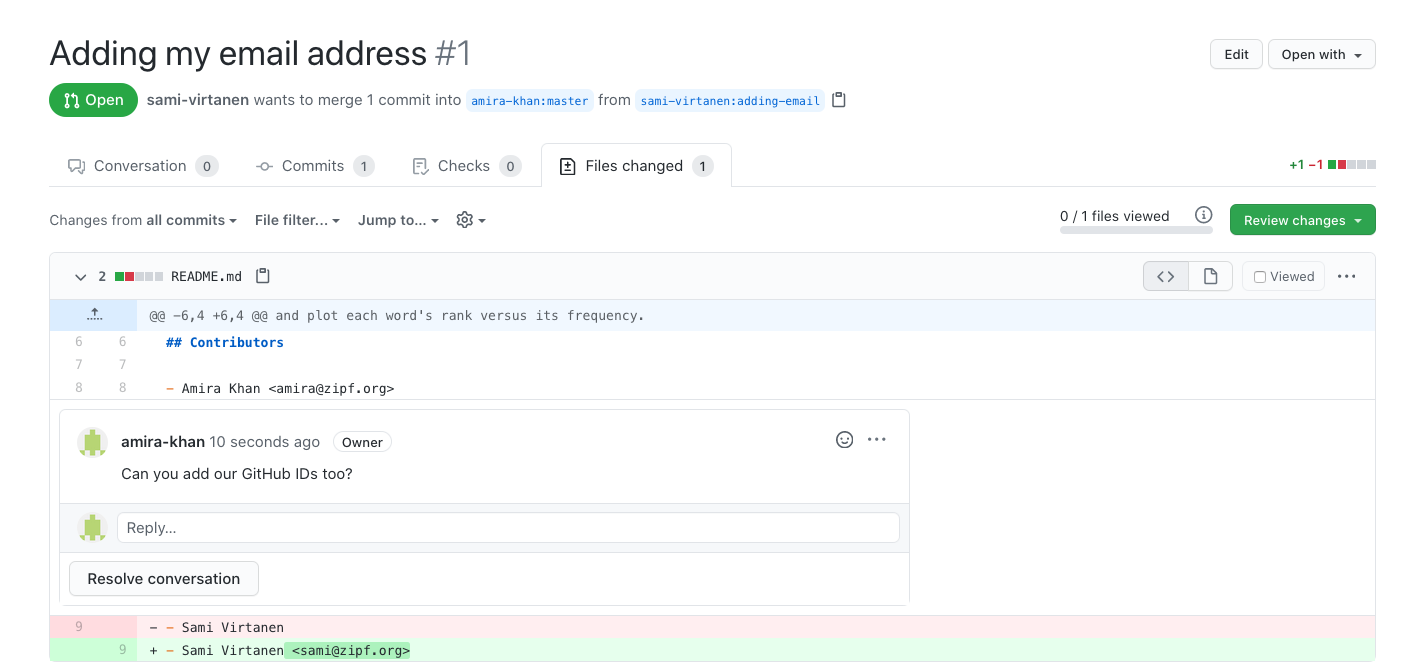

If she moves her mouse over particular lines, a white-on-blue cross appears near the numbers to indicate that she can add comments (Figure: Pull request - comment marker). She clicks on the marker beside her own name and writes a comment: She only wants to make one comment rather than write a lengthier multi-comment review, so she chooses “Add single comment” (Figure: Pull request - write a comment). GitHub redisplays the page with her remarks inserted (Figure: Pull Request with comment).

Fig. 33 Pull request comment marker#

Fig. 34 Pull request write a comment#

Fig. 35 Pull request with comment#

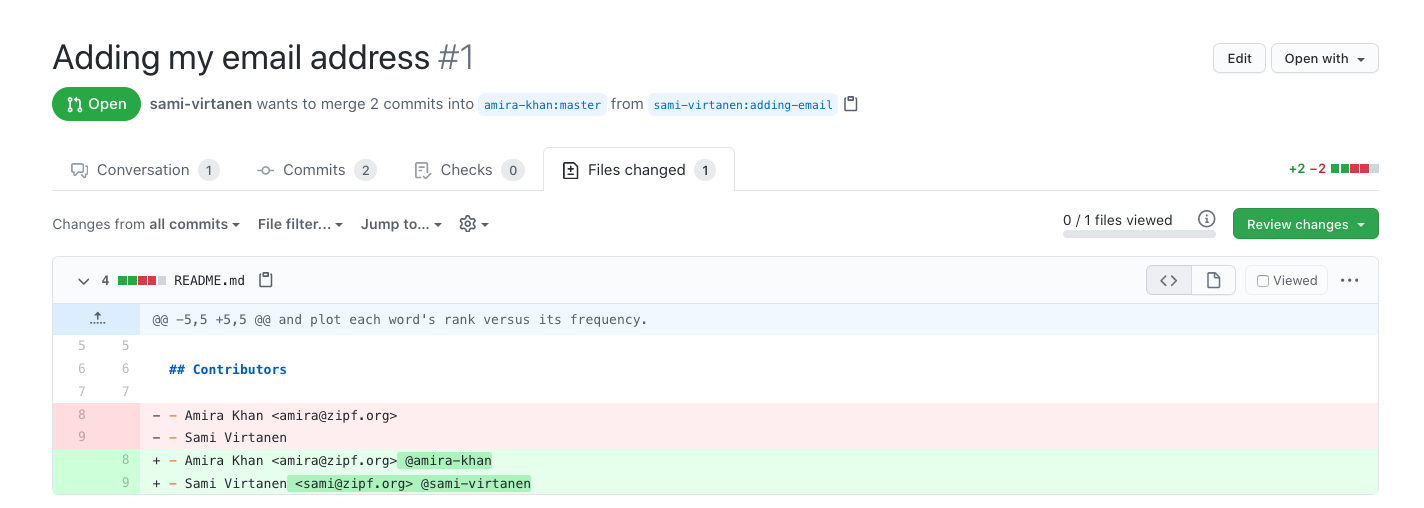

While Amira is working, GitHub has been emailing notifications to both Sami and Amira. When Sami clicks on the link in their email notification, it takes them to the PR and shows Amira’s comment. Sami changes README.md, commits, and pushes, but does not create a new pull request or do anything to the existing one.

As explained above, a PR is a note asking that two branches be merged,

so if either end of the merge changes, the PR updates automatically.

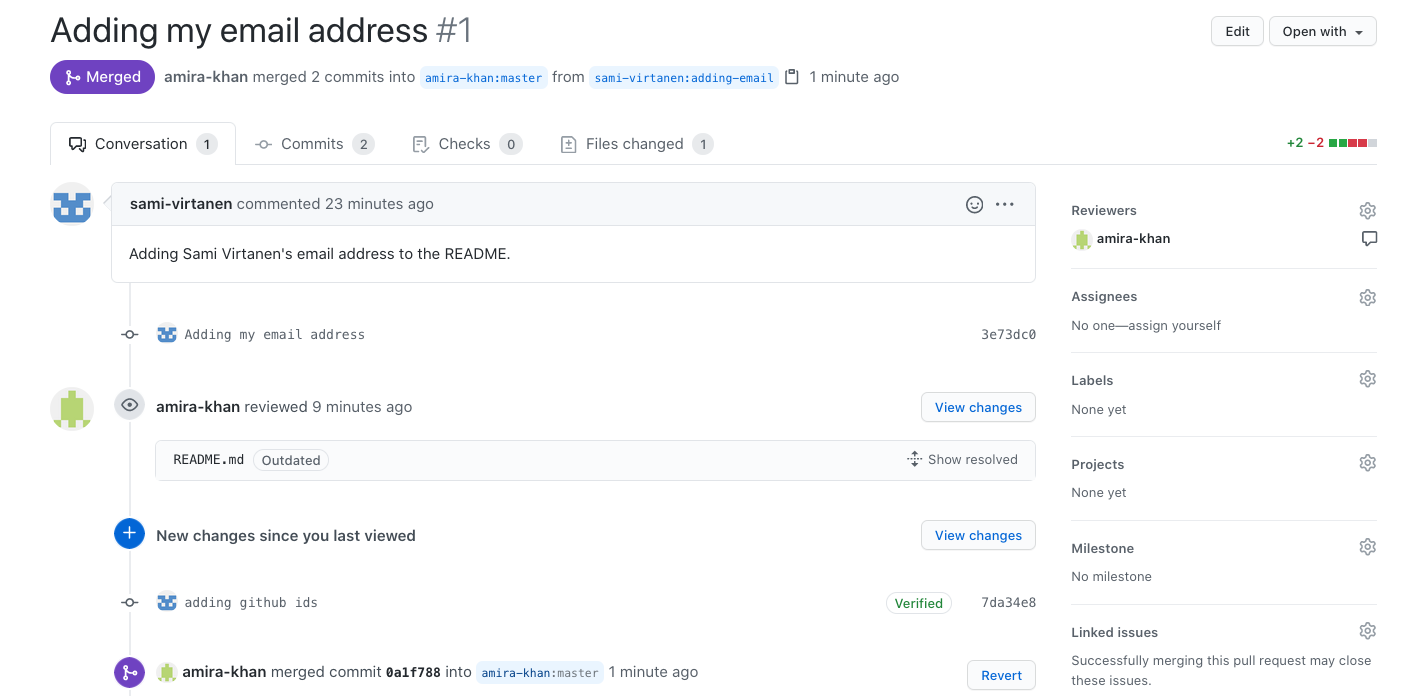

Sure enough, when Amira looks at the PR again a few moments later she sees Sami’s changes (Figure: Pull Request with fix). Satisfied, she goes back to the “Conversation” tab and clicks on “Merge”. The icon at the top of the PR’s page changes text and color to show that the merge was successful (Figure: - Pull Request - succesfull merge).

Fig. 36 Pull request with fix#

Fig. 37 PR successful merge#

To get those changes from GitHub to her desktop repository,

Amira uses git pull:

amira:~/zipf $ git pull origin master

From https://github.com/amira-khan/zipf

* branch master -> FETCH_HEAD

Updating 35fca86..a04e3b9

Fast-forward

README.md | 4 ++--

1 file changed, 2 insertions(+), 2 deletions(-)

To get the change they just made from their adding-email branch into their master branch, Sami could use git merge on the command line. It’s a little clearer, though, if they also use git pull from their upstream repository (i.e., Amira’s repository) so that they’re sure to get any other changes that Amira may have merged:

sami:~/zipf $ git checkout master

Switched to branch 'master'

Your branch is up to date with 'origin/master'.

sami:~/zipf $ git pull upstream master

From https://github.com/amira-khan/zipf

* branch master -> FETCH_HEAD

Updating 35fca86..a04e3b9

Fast-forward

README.md | 4 ++--

1 file changed, 2 insertions(+), 2 deletions(-)

Finally, Sami can push their changes back to the master branch

in their own remote repository:

sami:~/zipf $ git push origin master

Total 0 (delta 0), reused 0 (delta 0), pack-reused 0

To https://github.com/sami-virtanen/zipf.git

35fca86..a04e3b9 master -> master

All four repositories are now synchronized.

Handling Conflicts in Pull Requests#

Finally, suppose that Amira and Sami have decided to collaborate more extensively on this project. Amira has added Sami as a collaborator to the GitHub repository. Now Sami can make contributions directly to the repository, rather than via a pull request from a forked repository.

Sami makes a change to README.md in the master branch on GitHub.

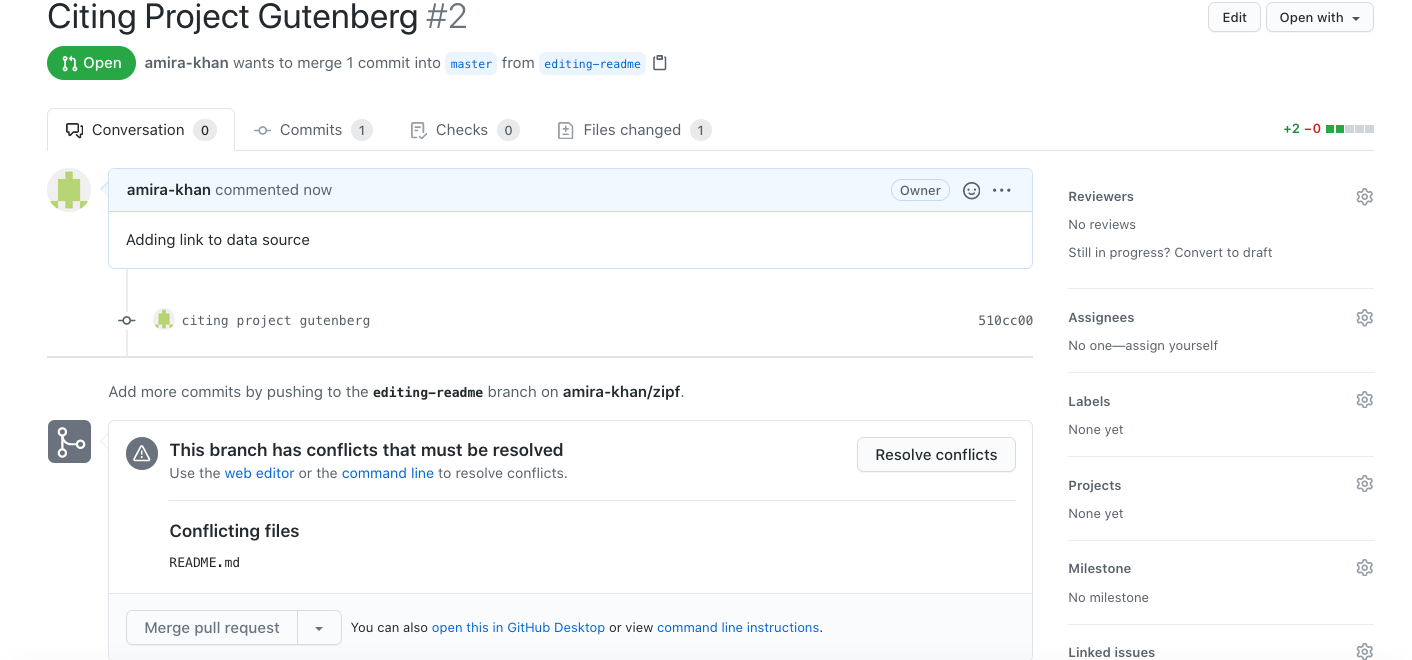

Meanwhile, Amira is making a conflicting change to the same file in a different branch. When Amira creates her pull request, GitHub will detect the conflict and report that the PR cannot be merged automatically (Figure: - Pull Request Conflict).

Fig. 38 Pull request conflict#

Amira can solve this problem with the tools she already has.

If she has made her changes in a branch called editing-readme, the steps are:

Pull Sami’s changes from the

masterbranch of the GitHub repository into themasterbranch of her desktop repository.Merge from the

masterbranch of her desktop repository to theediting-readmebranch in the same repository.Push her updated

editing-readmebranch to her repository on GitHub. The pull request from there back to themasterbranch of the main repository will update automatically.

GitHub and other forges do allow people to merge conflicts through their browser-based interfaces, but doing it on our desktop means we can use our favorite editor to resolve the conflict. It also means that if the change affects the project’s code, we can run everything to make sure it still works.

But what if Sami or someone else merges another change while Amira is resolving this one, so that by the time she pushes to her repository there is another, different, conflict? In theory this cycle could go on forever; in practice, it reveals a communication problem that Amira (or someone) needs to address. If two or more people are constantly making incompatible changes to the same files, they should discuss who’s supposed to be doing what, or rearrange the project’s contents so that they aren’t stepping on each other’s toes.