Handling Errors#

The Zipf’s Law project should now include:

zipf/

├── .gitignore

├── .travis.yml

├── CONDUCT.md

├── CONTRIBUTING.md

├── LICENSE.md

├── Makefile

├── README.md

├── requirements.txt

├── bin

│ ├── zipf.ipynb

│ ├── plotcount.py

│ ├── wordcount.py

│ ├── zipf_test.py.py

│ ├── plotparams.yml

│ ├── template.py

│

├── data

│ ├── dracula.txt

│ └── ...

├── results

│ ├── dracula.txt

│ ├── dracula.png

│ └── ...

├── test_data

│ ├── risk.txt

│ └── ...

├── test

│ ├── test_countwords.txt

│ └── ...

Exceptions#

Most modern programming languages use exceptions for error handling. As the name suggests, an exception is a way to represent an exceptional or unusual occurrence that doesn’t fit neatly into the program’s expected operation. The code below uses exceptions to report attempts to divide by zero:

for denom in [-5, 0, 5]:

try:

result = 1/denom

print(f'1/{denom} == {result}')

except:

print(f'Cannot divide by {denom}')

1/-5 == -0.2

Cannot divide by 0

1/5 == 0.2

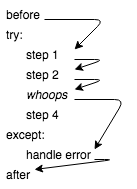

try/except looks like if/else and works in a similar fashion.

If nothing unexpected happens inside the try block,

the except block isn’t run (Figure Control Flow).

If something goes wrong inside the try,

on the other hand,

the program jumps immediately to the except.

This is why the print statement inside the try doesn’t run when denom is 0:

as soon as Python tries to calculate 1/denom,

it skips directly to the code under except.

Fig. 40 Control Flow#

We often want to know exactly what went wrong, so Python and other languages store information about the error in an object (which is also called an exception). We can catch an exception and inspect it as follows:

for denom in [-5, 0, 5]:

try:

result = 1/denom

print(f'1/{denom} == {result}')

except Exception as error:

print(f'{denom} has no reciprocal: {error}')

1/-5 == -0.2

0 has no reciprocal: division by zero

1/5 == 0.2

We can use any variable name we like instead of error;

Python will assign the exception object to that variable

so that we can do things with it in the except block.

Python also allows us to specify what kind of exception we want to catch. For example, we can write code to handle out-of-range indexing and division by zero separately:

numbers = [-5, 0, 5]

for i in [0, 1, 2, 3]:

try:

denom = numbers[i]

result = 1/denom

print(f'1/{denom} == {result}')

except IndexError as error:

print(f'index {i} out of range')

except ZeroDivisionError as error:

print(f'{denom} has no reciprocal: {error}')

1/-5 == -0.2

0 has no reciprocal: division by zero

1/5 == 0.2

index 3 out of range

Exceptions are organized in a hierarchy: for example,

FloatingPointError, OverflowError, and ZeroDivisionError

are all special cases of ArithmeticError,

so an except that catches the latter will catch all three of the former,

but an except that catches an OverflowError

won’t catch a ZeroDivisionError.

The Python documentation describes all of the built-in exception types;

in practice,the ones that people handle most often are:

ArithmeticError: something has gone wrong in a calculation.IndexErrorandKeyError: something has gone wrong indexing a list or lookup something up in a dictionary.OSError: thrown when a file is not found, the program doesn’t have permission to read it, and so on.

So where do exceptions come from? The answer is that programmers can raise them explicitly:

for number in [1, 0, -1]:

try:

if number < 0:

raise ValueError(f'no negatives: {number}')

print(number)

except ValueError as error:

print(f'exception: {error}')

1

0

exception: no negatives: -1

We can define our own exception types, and many libraries do, but the built-in types are enough to cover common cases.

One final note is that exceptions don’t have to be handled where they are raised.

In fact,

their greatest strength is that they allow long-range error handling.

If an exception occurs inside a function and there is no except for it there,

Python checks to see if whoever called the function is willing to handle the error.

It keeps working its way up through the call stack until it finds a matching except. If there isn’t one, Python takes care of the exception itself.

The example below relies on this:

the second call to sum_reciprocals tries to divide by zero,

but the exception is caught in the calling code

rather than in the function.

def sum_reciprocals(values):

result = 0

for v in values:

result += 1/v

return result

numbers = [-1, 0, 1]

try:

one_over = sum_reciprocals(numbers)

except ArithmeticError as error:

print(f'Error trying to sum reciprocals: {error}')

Error trying to sum reciprocals: division by zero

This behavior is designed to support a pattern called “throw low, catch high”: write most of your code without exception handlers, since there’s nothing useful you can do in the middle of a small utility function, but put a few handlers in the uppermost functions of your program to catch and report all errors.

We can now go ahead and add error handling to our Zipf’s Law code.

Some is already built in:

for example,

if we try to read a file that does not exist,

the open function throws a FileNotFoundError:

$ python bin/collate.py results/none.txt results/dracula.txt

Traceback (most recent call last):

File "bin/collate.py", line 35, in <module>

main(args)

File "bin/collate.py", line 23, in main

with open(fname, 'r') as reader:

FileNotFoundError: [Errno 2] No such file or directory:

'results/none.csv'

But what happens if we try to read a file that exists,

but was not created by wordcount.py?

$ python bin/collate.py Makefile

Traceback (most recent call last):

File "bin/collate.py", line 35, in <module>

main(args)

File "bin/collate.py", line 24, in main

update_counts(reader, word_counts)

File "bin/collate.py", line 15, in update_counts

for word, count in csv.reader(reader):

ValueError: not enough values to unpack (expected 2, got 1)

This error is hard to understand,

even if we are familiar with the code’s internals.

Our program should therefore check that the input files are CSV files,

and if not,

raise an error with a useful explanation of what went wrong.

We could achieve this by wrapping the call to open in a try/except clause:

for fname in args.infiles:

try:

with open(fname, 'r') as reader:

update_counts(reader, word_counts)

except ValueError as e:

print(f'{fname} is not a txt file.')

print(f'ValueError: {e}')

$ python bin/collate.py Makefile

Makefile is not a txt file.

ValueError: not enough values to unpack (expected 2, got 1)

This is definitely more informative than before.

However,

all ValueErrors that are raised when trying to open a file

will result in this error message,

including those raised when we actually do use a CSV file as input.

A more precise approach in this case would be to throw an exception

only if some other kind of file is specified as an input:

for fname in args.infiles:

if fname[-4:] != '.txt':

raise OSError(f'{fname} is not a txt file.')

with open(fname, 'r') as reader:

update_counts(reader, word_counts)

$ python bin/collate.py Makefile

Traceback (most recent call last):

File "bin/collate.py", line 37, in <module>

main(args)

File "bin/collate.py", line 24, in main

raise OSError(f'{fname} is not a CSV file.')

OSError: Makefile is not a CSV file.

This approach is still not perfect:

we are checking that the file’s suffix is .txt

instead of checking the content of the file

and confirming that it is what we require.

What we should do is check that there are two columns separated by a comma,

that the first column contains strings,

and that the second is numerical.

Kinds of Errors

The “

ifthenraise” approach is sometimes referred to as “look before you leap,” while thetry/exceptapproach obeys the old adage that “it’s easier to ask for forgiveness than permission.” The first approach is more precise, but has the shortcoming that programmers can’t anticipate everything that can go wrong when running a program, so there should always be anexceptsomewhere to deal with unexpected cases.The one rule we should always follow is to check for errors as early as possible so that we don’t waste the user’s time. Few things are as frustrating as being told at the end of an hour-long calculation that the program doesn’t have permission to write to an output directory. It’s a little extra work to check things like this up front, but the larger your program or the longer it runs, the more useful those checks will be.

Writing Useful Error Messages#

Fig. 41 Error message#

The error message shown in Figure Error Message is not helpful.

Having collate.py print the message below would be equally unfriendly:

OSError: Something went wrong, try again.

This message doesn’t provide any information on what went wrong, so it is difficult to know what to change for next time. A slightly better message would be:

OSError: Unsupported file type.

This tells us the problem is with the type of file we’re trying to process,

but it still doesn’t tell us what file types are supported,

which means we have to rely on guesswork or read the source code.

Telling the user “filename is not a TXT file”

(as we did in the previous section)

makes it clear that the program only works with CSV files,

but since we don’t actually check the content of the file,

this message could confuse someone who has comma-separated values saved in a .txt file.

An even better message would therefore be:

OSError: File must end in .txt

This message tells us exactly what the criteria are to avoid the error.

Error messages are often the first thing people read about a piece of software, so they should therefore be the most carefully written documentation for that software. A web search for “writing good error messages” turns up hundreds of hits, but recommendations are often more like gripes than guidelines and are usually not backed up by evidence. What research there is gives us the following rules [Becker et al., 2016]:

Tell the user what they did, not what the program did. Putting it another way, the message shouldn’t state the effect of the error, it should state the cause.

Be spatially correct, i.e., point at the actual location of the error. Few things are as frustrating as being pointed at line 28 when the problem is really on line 35.

Be as specific as possible without being or seeming wrong from a user’s point of view. For example, “file not found” is very different from “don’t have permissions to open file” or “file is empty.”

Write for your audience’s level of understanding. For example, error messages should never use programming terms more advanced than those you would use to describe the code to the user.

Do not blame the user, and do not use words like fatal, illegal, etc. The former can be frustrating—in many cases, “user error” actually isn’t—and the latter can make people worry that the program has damaged their data, their computer, or their reputation.

Do not try to make the computer sound like a human being. In particular, avoid humor: very few jokes are funny on the dozenth re-telling, and most users are going to see error messages at least that often.

Use a consistent vocabulary. This rule can be hard to enforce when error messages are written by several different people, but putting them all in one module makes review easier.

That last suggestion deserves a little elaboration. Most people write error messages directly in their code:

if fname[-4:] != '.txt':

raise OSError(f'{fname}: File must end in .txt')

A better approach is to put all the error messages in a dictionary:

ERRORS = {

'not_txt_suffix' : '{fname}: File must end in .txt',

'config_corrupted' : '{config_name} corrupted',

# ...more error messages...

}

and then only use messages from that dictionary:

if fname[-4:] != '.txt':

raise OSError(ERRORS['not_txt_suffix'].format(fname=fname))

Doing this makes it much easier to ensure that messages are consistent. It also makes it much easier to give messages in the user’s preferred language:

ERRORS = {

'en' : {

'not_txt_suffix' : '{fname}: File must end in .txt',

'config_corrupted' : '{config_name} corrupted',

# ...more error messages in English...

},

'fr' : {

'not_txt_suffix' : '{fname}: Doit se terminer par .txt',

'config_corrupted' : f'{config_name} corrompu',

# ...more error messages in French...

}

# ...other languages...

}

The error report is then looked up and formatted as:

ERRORS[user_language]['not_txt_suffix'].format(fname=fname)

where user_language is a two-letter code for the user’s preferred language.

Testing Error Handling#

An alarm isn’t much use if it doesn’t go off when it’s supposed to.

Equally,

if a function doesn’t raise an exception when it should

then errors can easily slip past us.

If we want to check that a function called func

raises an ExpectedError exception,

we can use the following template for a unit test:

#...set up fixture...

try:

actual = func(fixture)

assert False, 'Expected function to raise exception'

except ExpectedError as error:

pass

except Exception as error:

assert False, 'Function raised the wrong exception'

\newpage

This template has three cases:

If the call to

funcreturns a value without throwing an exception then something has gone wrong, so weassert False(which always fails).If

funcraises the error it’s supposed to, then we go into the firstexceptbranch without triggering theassertimmediately below the function call. The code in thisexceptbranch could check that the exception contains the right error message, but in this case it does nothing (which in Python is writtenpass).Finally, if the function raises the wrong kind of exception we also

assert False. Checking this case might seem overly cautious, but if the function raises the wrong kind of exception, users could easily fail to catch it.

This pattern is so common that pytest provides support for it.

Instead of the eight lines in our original example,

we can write:

import pytest

#...set up fixture...

with pytest.raises(ExpectedError):

actual = func(fixture)

The argument to pytest.raises is the type of exception we expect;

the call to the function then goes in the body of the with statement.

We will explore pytest.raises further in the exercises.

Reporting Errors#

Programs should report things that go wrong;

they should also sometimes report things that go right

so that people can monitor their progress.

Adding print statements is a common approach,

but removing them or commenting them out when the code goes into production is tedious and error-prone.

A better approach is to use a logging framework, such as Python’s logging library.

This lets us leave debugging statements in our code

and turn them on or off at will.

It also lets us send output to any of several destinations,

which is helpful when our data analysis pipeline has several stages

and we are trying to figure out which one contains a bug.

To understand how logging frameworks work,

suppose we want to turn print statements in our collate.py program on or off

without editing the program’s source code.

We would probably wind up with code like this:

if LOG_LEVEL >= 0:

print('Processing files...')

for fname in args.infiles:

if LOG_LEVEL >= 1:

print(f'Reading in {fname}...')

if fname[-4:] != '.txt':

msg = ERRORS['not_txt_suffix'].format(fname=fname)

raise OSError(msg)

with open(fname, 'r') as reader:

if LOG_LEVEL >= 1:

print(f'Computing word counts...')

update_counts(reader, word_counts)

LOG_LEVEL acts as a threshold:

any debugging output at a lower level than its value isn’t printed.

As a result,

the first log message will always be printed,

but the other two only in case the user has requested more details

by setting LOG_LEVEL higher than zero.

A logging framework combines the if and print statements in a single function call

and defines standard names for the logging levels.

In order of increasing severity,

the usual levels are:

DEBUG: very detailed information used for localizing errors.INFO: confirmation that things are working as expected.WARNING: something unexpected happened, but the program will keep going.ERROR: something has gone badly wrong, but the program hasn’t hurt anything.CRITICAL: potential loss of data, security breach, etc.

Each of these has a corresponding function:

we can use logging.debug, logging.info, etc. to write messages at these levels.

By default,

only WARNING and above are displayed;

messages appear on standard error so that the flow of data in pipes isn’t affected.

The logging framework also displays the source of the message,

which is called root by default.

Thus,

if we run the small program shown below,

only the warning message appears:

import logging

logging.warning('This is a warning.')

logging.info('This is just for information.')

WARNING:root:This is a warning.

Rewriting the collate.py example above using logging

yields code that is less cluttered:

import logging

logging.info('Processing files...')

for fname in args.infiles:

logging.debug(f'Reading in {fname}...')

if fname[-4:] != '.txt':

msg = ERRORS['not_txt_suffix'].format(fname=fname)

raise OSError(msg)

with open(fname, 'r') as reader:

logging.debug('Computing word counts...')

update_counts(reader, word_counts)

We can also configure logging to send messages to a file

instead of standard error

using logging.basicConfig.

(This has to be done before we make any logging calls—it’s not retroactive.)

We can also use that function to set the logging level:

everything at or above the specified level is displayed.

import logging

logging.basicConfig(level=logging.DEBUG, filename='logging.log')

logging.debug('This is for debugging.')

logging.info('This is just for information.')

logging.warning('This is a warning.')

logging.error('Something went wrong.')

logging.critical('Something went seriously wrong.')

DEBUG:root:This is for debugging.

INFO:root:This is just for information.

WARNING:root:This is a warning.

ERROR:root:Something went wrong.

CRITICAL:root:Something went seriously wrong.

By default,

basicConfig re-opens the file we specify in append mode;

we can use filemode='w' to overwrite the existing log data.

Overwriting is useful during debugging,

but we should think twice before doing it in production,

since the information we throw away often turns out to be

exactly what we need to find a bug.

Many programs allow users to specify logging levels and log filenames as command-line parameters.

At its simplest,

this is a single flag -v or --verbose that changes the logging level from WARNING (the default)

to DEBUG (the noisiest level).

There may also be a corresponding flag -q or --quiet that changes the level to ERROR,

and a flag -l or --logfile that specifies the name of a log file.

To log messages to a file while also printing them,

we can tell logging to use two handlers simultaneously:

import logging

logging.basicConfig(

level=logging.DEBUG,

handlers=[

logging.FileHandler("logging.log"),

logging.StreamHandler()])

logging.debug('This is for debugging.')

The string 'This is for debugging' is both printed to standard error

and appended to logging.log.

Libraries like logging can send messages to many destinations;

in production,

we might send them to a centralized logging server

that collates logs from many different systems.

We might also use rotating files

so that the system always has messages from the last few hours

but doesn’t fill up the disk.

We don’t need any of these when we start,

but the data engineers and system administrators

who eventually have to install and maintain your programs

will be very grateful if we use logging instead of print statements,

because it allows them to set things up the way they want with very little work.

Logging Configuration

Chapter on Configuration explained why and how to save the configuration that produced a particular result. We clearly also want this information in the log, so we have three options:

Write the configuration values into the log one at a time.

Save the configuration as a single record in the log (e.g., as a single entry containing JSON).

Write the configuration to a separate file and save the filename in the log.

Option 1 usually means writing a lot of extra code to reassemble the configuration. Option 2 also often requires us to write extra code (since we need to be able to save and restore configurations as JSON as well as in whatever format we normally use), so on balance we recommend option 3.

Summary#

Most programmers spend as much time debugging as they do writing new code, but most courses and textbooks only show working code, and never discuss how to prevent, diagnose, report, and handle errors. Raising our own exceptions instead of using the system’s, writing useful error messages, and logging problems systematically can save us and our users a lot of needless work.

Keypoints#

Signal errors by raising exceptions.

Use

try/exceptblocks to catch and handle exceptions.Python organizes its standard exceptions in a hierarchy so that programs can catch and handle them selectively.

“Throw low, catch high,” i.e., raise exceptions immediately but handle them at a higher level.

Write error messages that help users figure out what to do to fix the problem.

Store error messages in a lookup table to ensure consistency.

Use a logging framework instead of

printstatements to report program activity.Separate logging messages into

DEBUG,INFO,WARNING,ERROR, andCRITICALlevels.Use

logging.basicConfigto define basic logging parameters.